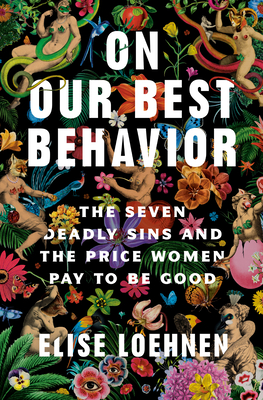

Today’s guest is author, editor, and former GOOP COO Elise Loehnen. Elise shares how a simple conversation around sin led her to her latest book, “On Our Best Behavior.” Prepare to explore the profound influence of the “7 Deadly Sins” (with a twist) on our daily beliefs, reactions, and behaviors—covering anger, laziness, pride, lust, envy, greed, and gluttony.

We also delve into the intriguing backstory of why there are 8 sins instead of 7. Elise shares the fascinating origin, where an Egyptian Monk crafted the original list known as the “eight thoughts.” Curiously, sadness was later omitted from the lineup.

But our conversation doesn’t stop there. Elise opens up about her experiences working behind the scenes, whether it be ghostwriting books for others or being instrumental in building a brand. She sheds light on her decision to step out from the shadows and share her own voice and perspective through her latest work. Together, we explore the meaning of contributing to a company’s growth and the personal journey of choosing a different path.

Join us for this insightful discussion as we uncover the secrets behind human behavior and personal growth. Whether you’re seeking knowledge, inspiration, or simply trying to figure it all out, this episode has something for everyone.

A Mother of two sons, a wife, and just like all of us trying to figure it out. I hope you enjoy our conversation.

Listen to the episode here:

[podcast_subscribe id=”5950″]

Key Topics:

- The Seven Deadly Sins [00:04:43]

- Why Elise Wrote the Book [00:15:22]

- On Greed: What Do You Need and Want? [00:22:55]

- On Envy: Women Against Women [00:36:29]

- Pay Attention to the Envy [00:42:44]

- On Sloth: Women in Self-Policing [00:55:54]

- On Pride: Humility and False Modesty [01:02:02]

- Mothers and the Notion of Service [01:07:45]

- On Gluttony: Weight is Not Health [01:16:48]

- On Lust: Women on Connecting with Themselves [01:25:16]

- On Anger: Women and Processing Anger [01:33:26]

- Developing Emotional IQ [01:42:10]

- On Sadness: The Eighth Thought [01:43:39]

- Writing the Hardest and Easiest Chapter [01:48:44]

- Wellness vs. Wholeness [01:53:00]

- Elise’s Book Recommendations [01:58:05]

#202 The Price Tag of ‘Being Good’: Author and Former GOOP COO Elise Loehnen on How Women Navigate Societal Expectations + Embracing Your True Identity, Transforming Shame into a Path of Self-Discovery & Redefining Power and Identity

Welcome to the Gabby Reece Show where we break down the complex worlds of health, fitness, family, business, and relationships with the world’s leading experts. I’m here to simplify these topics and give you practical takeaways that you can start using today. We all know that living a healthy balanced life isn’t always easy. Let’s try working on managing life a little better and have some fun along the way. After all, life is one big experiment and we’re all doing our best.

—

“The way that women are told to be a good woman and a good mother, these are the social structures or parameters or this is what it looks like to perform that role publicly and ritually. I don’t that that aligns with who we are. The same with men, I can’t speak as much of that experience because I’m not one. There is a certain balance in all of us, regardless of our gender. There are gender differences and physical differences. Where we bristle or where we get confined is when there are these ideas about how a woman should behave and how a man should behave. The reality is we’re far more interesting than that.”

—

My guest is author, Elise Loehnen. Her book, On Our Best Behavior, comes from a fascinating place. She’s having a conversation with somebody about envy. All of us are taught envy is bad and it’s not good. Especially if you’re a female, it’s like, “That’s not nice.” The person she was talking to was like, “Also, it’s an indication that you’re not maybe doing something you would like to be doing in your life. Could you flip it and use it as an electric arrow?” It’s like, “Over here, maybe you should be doing this, and why aren’t you?”

Being a smarty-pants, she went to Yale, and she’s been an editor and author. She was the COO of Goop. She started to dig deeper into, where does envy come from? That brought her to the 7 sins but there are 8, and they are sloth, envy, pride, which is known to be the worst, gluttony, greed, lust, anger, and the one that they left off is sadness. All of us think that these are in the Bible but they’re not. This was originally written by a monk in Egypt and it was called the Eight Thoughts. This somehow was turned into the seven deadly sins, minus sadness, and then put on us culturally. If you’re angry, that’s not good.

For women, for example, look desirable but don’t have a desire. She peels this back. Especially for women, we’re interested in being nice or good, whatever that means. If we can be honest more with ourselves or not beat ourselves up, for example, with gluttony or sloth, it’s like, “Maybe I need to take a break. Maybe I’m tired. Maybe I can’t get it all done today.” Not only would we be living a life that reflected who we were but would be better for all of us. It would be more honest and more clear and maybe we wouldn’t have all these packed-in feelings.

Even though this conversation is skewed more toward females, this is true for all of us. We live in a world where everybody has a comment on everything or we do what we’re supposed to do so we can be achieving, successful, or good people. Where did this come from and why is it still there? Can we make our way out of it? The book is called On Our Best Behavior. I learned a lot. We’re not going to have the same exact opinion.

It was fun to ask her what she thought about different in certain things and move it toward a positive thing. This is the other important thing for me about this conversation, this is not about blaming anyone, this is about saying, “How did we get here? What can we improve upon? Let’s get to it so we can all feel and be our best.” I hope you enjoy my conversation with Elise Loehnen.

—

Elise Loehnen, welcome to my home.

Thanks for having me.

Congratulations on your book.

Thank you.

I’ve read your book and I want to congratulate you on writing a beautiful book. You managed to make an invitation to change. It’s not a blame game book. It’s like, “This is how we got here, this is how it shows, and maybe this is how we could do it better.” I appreciate that. we’re in a time right now where we don’t know how to invite each other to look at things in a different way without it being someone’s fault. You managed to do this. It’s informative too. I was like, “That’s right. It should be pride and anger.” Let’s talk about the seven deadly sins. We hear The 10 Commandments and we think, “The seven deadly sins are part of the Bible,” but in fact, they’re not. They were written by Eight Thoughts.

An Egyptian monk in the desert in the 4th century, the same time that the New Testament was being canonized, and when they were determining which gospels would be in the canon and which were not. They were in the atmosphere and they were being passed around. He wrote them down and then they traveled around through the Desert Fathers until they made it to Rome in the 6th century and that’s when they entered the religion.

Like you, I always assumed they were somewhere in the Bible. I’m not extremely well versed in the Bible but they’re fanfic to quote my friend, she was like, “These sins are fanfic,” and they are. Yet, what I observed once I looked them up is that they are deep in our consciousness as a checklist for goodness. It’s not even that anyone is overtly insisting on them in our lives. We don’t have to be part of any religion in order for this to be true. It’s that we abide by them and pass them on to each other without conscious awareness.

I love that you got from the book that there’s no one to blame because, in our polarized binary culture where most of us are stuck and frustrated, there is no enemy. It’s not the fault of “all men.” One of the motivating forces too is that you can look out at our society and observe all the inequities, the pay gap, the wealth gap, which is $0.32 cents to the dollar. We see it and feel it and yet I look around and I’ve loved the men that I’ve worked for.

[bctt tweet=”We have this default assumption about women. What I hope for all of us is that we all get that freedom to define it for ourselves.”]

I am the mother to two boys. I’m married to a sweet and gentle man. It was hard sometimes to identify, “It’s this person.” There are problematic men in our culture and there are problematic women but to me, it wasn’t about railing against the systems out there as much as it was addressing what was happening in here and this cult of goodness that we’re subscribed to that limits our lives and keeps us from full expression.

I’m a female and I have three daughters and it’s an interesting conversation. First of all, let’s remind people about the sins in case we’ve forgotten. Maybe sloth would be laziness, envy, pride, which supposedly is the worst of all, gluttony, greed, lust, anger, and sadness. We’ll get into those to give people a quick reminder. When you decided to take this on, there’s an interesting nuance.

Let’s say you’re a well-educated and professional woman. You had a big job at Goop. You’ve had other important jobs. In status, as far as in your home, you’ve chosen partnership. You went to a good school and all these things. With me, coming from athletics and having a partner that is truly a partner, it’s the idea of modern, whatever that means, or being strong. Forward facing, we both Probably represent that in certain ways. There’s an interesting dance even for someone like us.

First of all, where did I get those feelings? Secondly, how much of it is the way my brain works versus the way someone else’s brain works, the biology of it? In this show, for example, I talk a lot about science-y biology movement. I’m interested in the notion of health and wellness but not in that canned way, but in that deeper, “What systems are in play?” I can’t help but think in certain ways.

There are always exceptions. Some of this is the way our brain is or tribal living if everyone else was to go on hunting and you and I were there and we had to get along with everyone. Also, there’s a nuance to this to be examined besides probably a group of guys a long time ago got together and thought, “Between them physically overall being physically a little bit weaker and having biological responsibilities, we could put a system in place that would work well for us.” It’s an interesting thing.

It’s the crux of it and it’s this idea of what’s biology, what’s culture, how does culture drive biology, directly, and then how you tease them apart. You’re a model for all of us, a strong and tall woman out in the world modeling a more modern and progressive partnership too. You are not someone I would imagine in Paleolithic times hiding out in a cave. We’re sold this story about who we are.

It’s important to understand both technically how our biology or how our natures have been shaped by culture and also, what’s more culture than nature and who are we. For example, patriarchy, which is a boogeyman word, what does that even mean? It hasn’t always been the way. A lot of women are like, “There were matriarchies.” It’s like, “Not really.” There’s no evidence of a dominance-based culture where women are oppressive towards men. That doesn’t exist.

We’re working on it right now.

Affiliative partnership-style cultures did exist. It’s fascinating when you go into the evidence about who we were back in our pre-history. You go to Çatalhöyük in modern-day Turkey in Anatolia and when Stanford anthropologists have examined the remains of people there, men and women are essentially the same size. Men weren’t getting a lot of calories or better calories, which you see in some cultures.

Obviously, culture is different everywhere. They have the same amount of soot in their lungs, which suggests that they were doing an equal amount of kitchen time or indoor time. In the Andes, when they had examined these 26 graves of warriors and they had always thought they were men, and when they went back in there with new technology, 10 of the 26 were women. There are female vikings, etc.

Have you ever seen the race, it’s four people and it’s brutal. The teams that do the best always have one woman. It’s 3 guys and 1 woman. Is she the voice of reason or will she be the one person that when they’re all arguing, she goes, “Can we stop this?” To your point, and you talk about it in the book, divine of either.

The divine masculine, energetically, isn’t meaning male, divine feminine. These are the qualities and the highest frequency of these traits versus males, females, and breaking that down. In a way, that’s what we abandon when we make these rules. For example, the most well-balanced males or ones that possess these notions of divine masculinity, what is that? Protectiveness for the collective.

Structure, order, and truth.

They have a tendency to be the most feminine as well, have that caring. It’s an interesting thing where I feel like almost civilized living has made us a hodgepodge and we don’t know how to house that within ourselves. I think about that a lot. When I read this, I was like, “Part of it is we’ve lost a lot of the extremes of both.” What you’re saying is, in these places, you have men and women being together. Why did you want to write this?

I had, in some ways, run myself to the end of my chain or leash. That’s probably not even the right metaphor. I am a high-performance person. Throughout my life, I have achieved in all spheres academically and physically. I always wanted to be a good perfectionistic girl and then a woman. I had a moment in 2019 and early 2020 before the pandemic when I had been with my therapist and I had been in the middle of this long hyperventilator.

It’s not in the breathing into the bag way but in the ongoing disconnect between my brain and my body where I perceive myself as not having enough oxygen. Meanwhile, I’m over breathing. I can’t take deep breaths because my lungs are over-full. I can guarantee you that there are people reading who have this disorder and have never been diagnosed. When I get stressed, run-down, tired, or over-caffeinated, I cannot take a deep breath until I yawn. I will start doing this and I will do it for days. In this particular instance, I had been doing it for more than a month and it is exhausting.

What does that look like? You wake up in the morning and you’re sitting with your husband. Do you start right away into that?

I usually wake up and I’m doing better and then by lunchtime, I can’t take a deep breath until I yawn, and then I become conscious of it and it becomes more exhausting for me when I’m bringing my attention to the fact that I cannot breathe. I can still exercise. I’m certainly oxygenated but I have this feeling of asphyxiation. When it first started happening to me in my 20s, I went to the emergency room. My dad is a pulmonologist. They told me what was happening, they gave me some Xanax, they set me on my way, and it has plagued me ever since until it got to the point where I couldn’t keep living like that.

The connection I made with my therapist that day was that I had been driving myself to this idea that at some point, I would be safe, secure, and enough that I would outrun this anxiety disorder and be able to breathe. The revelation in the office that day was that there was no way. I wasn’t going to outrun it and I had to understand it and get my arms around it. That’s where the idea started, “What is this voice in me that is telling me that I’m not enough? What is this?” Despite having two great kids, a great job, and, theoretically and overtly, a successful career. It brought me to my knees in a way, “This is not how I want to live.” You could call it the inner critic but it was many different voices.

When you say many different?

Sloth, for example, you’re lazy or you’re not doing enough. It was old sexual trauma. It was the way that I would shame myself about my body. Ultimately, it emerged as the sins. At the time, I was trying to figure out where it was, where it started, what was it, and why was it alive in me insistently.

Elise Loehnen – Anger is often a secondary emotion to fear, shame, and grief. When we can’t process our anger, we can’t access even those even deeper emotions, which we need to move.

You transitioned out of the then job that you were doing, which would be a coveted job to have. You were doing podcasts for Goop. You were doing Netflix shows. You were the COO of the company. You were doing everything that we think we’re supposed to be doing. First of all, how do you get the balls to walk away from that?

Everything changed. It was COVID, which, like many people, fortunately, I didn’t experience the deep bottom of Covid. I certainly experienced both the scary parts of it and also the opportunity that came to us in it. That’s maybe an outrageous thing to say but I needed that stop sign.

It was a complete break in so many ways.

It was this moment of having, prior to Covid, been traveling almost every week to being grounded and being at home with all of the things in my house and my kids and my husband and having to confront myself. Once the busyness was gone, it was time to address all of the stuff that was alive in me that needed to come up. Part of it is, I write about this extensively, in pride. More or less, not in every single moment, but I’ve spent a lot of my life hiding behind other people.

Do you mean propping other people up?

Ghost writing. I’ve ghost-written or co-written twelve books, which I love to do, working for brands, and working at magazines with no bylines. That was always my preference. I never tried to be a writer under my own name. It’s a theme throughout my whole career relying on other people to structure my life. I knew I needed to stand behind myself and allow myself to be the author or authority instead of trying to pass all of my creative energy on to other people. That’s hard. It was a big shift for me.

One of the first things I wrote down is that when you were questioning your feelings finally, it cost you a lot. I was like, “That is such an interesting thing.” When we get to the place where we say, “We’re going to take a look at it,” it’s scary sometimes, like, “Then, what position and decisions are we going to have to make? What changes?” I admire that you pulled the hand break.

A big part of it was doing a basic audit, which anyone can benefit from. I work with this woman, Krista Schumacher. She’s a spiritual teacher. I don’t know if you’ve encountered her yet. I was talking to her and this was early on in this process. I was saying to her in a certain franticness, “I don’t know. I won’t have enough,” and all of this stuff that we know well, “I’ll never have enough.”

She said to me, “What do you need and what do you want? Can you please write it down? I promise you can meet your needs.” I had never done that. I’d made a basic budget at some point in my life but I had more or less been winging it while this constant feeling of scarcity and, “Go, go, go, go, go. I need more,” without quantifying any of it. When I sat and I wrote down, I did it in two versions, I did my practical needs and some practical wants, and I had a revelation.

What’s a practical want?

Like, “I want a new car. I want to go on vacation with my kids twice a year to Montana.” It’s stuff like that, which you could say is a need in some ways too. I did the practical version of writing things down, which I highly recommend to everyone. When I looked at my needs and my wants, I realized I could do it, and I could get my arms around it. It was very calming for me and very concretized this anxiety and emotion. I also needed to get in touch with my wanting on a deeper level.

I feel like a lot of women are disconnected from our wanting. We’ve been conditioned to not have any wants at all and to subjugate our wants to other people’s needs. This is primary programming for women in our culture. This is a big part of what envy is about but I had to identify what I want. For me, it is writing books, hosting a podcast, and maybe a little bit of consulting. If I can do that and make that work and meet my needs, that is what I want. For some people, they want to fill a stadium. Some people want a magazine cover. I don’t want that. I want to write books, host a podcast, and write my weekly newsletter. It’s interesting how even that was hard to admit to myself or to arrive there.

You didn’t think you had earned the right to say, “This is what I want.” There’s something else interesting. Losing is hard and so is winning. I am interested to get into envy. Sometimes with winning comes separation. I don’t want to over-categorize. Men suffer this way less. I had a volleyball coach, Gary Sato. He told a great story once. He was an assistant coach to a men’s USA men’s volleyball team. An incredible coach, Marv Dunphy, told the team they we’re in a tight spot playing internationally.

He looked at this guy, Karch Kiraly, and said, “You’re going to take the ball. You’re going to put the ball away. You got to do this.” The whole team did it. Karch puts the ball. Gary thought to himself, “I’m going to pocket this for another time.” Fast forward, he’s coaching some high-level women’s team, he picks the player that’s the one for the play, and everybody moves away. She was like, “Don’t be singling me out here in this moment.”

There’s an interesting thing where none of us want to lose and I don’t mean it in the game, I mean in life. Yet, winning is a whole other set of things, “What if I do know what I want and I try to get it or I get it?” I’m always so intrigued by that. For you to be able to say, “This is what I want.” By the way, based on your entire body of work, it seems reasonable. It’s not a stretch. Not only that, it seems like that makes sense and you should. I always find it so interesting that was even hard for you to get to.

It’s kind of sad.

No. It’s all fascinating. The other thing is how do we start to move through life and go through these experiences and feel it and not be like, “That’s good or bad.” Be like, “Maybe that’s not working for me. It doesn’t serve me so I’m going to stop doing that.” It is funny, that was like, “This is what I want to do.” It’s like, “Yeah, great. Of course.”

Standing out, the exclusionary part of winning that you keyed into is significant for women. It’s partially about the scarcity of opportunity and not as many women. There is something in us too. Pride is about in every sector and I hadn’t thought about it in terms of athletics but it’s true too. Culturally, the messaging is loud and clear. As much as we look at our most visible women, famous women, and we celebrate them when they’re the underdogs and they’re coming up and then they hit a certain point where we decide, “That’s enough.” We take them down culturally.

We all participate in this and we think of them as separate from us or that it’s not the same as us. All we’re doing is creating this narrative about women who get too big for their britches, women who need to be put back in their place, and women who dare to be seen. It trickles down into the lives of all of us. It’s what we’re modeling for girls. We have a right. It’s completely reasonable that the volleyball player is like, “I am not going first. Do not separate me from the crowd.” “

“I’m on a team.” That’s the other thing too. Also, inherently there’s such cooperation among women. We pull it. It’s like, “I need a doctor. Have you ever gone through this? This is happening.” That’s how we pull it. How do we do both at the same time? How do we be special and strong and in pursuit and then be of the one and of the collective? That feels like the natural rhythm and flow if we could do it in an ideal way.

I remember him telling me that and I was like, “That makes sense.” If she happened to set the ball and put the ball away and was the one, that’s great, the team wins. At the moment, prior to, it’s like, “You’re going to be the one.” It was like, “Wait a second.” I’ll tell you the only athletes I’ve never seen have this problem, for me personally, and probably fighters don’t have it, are downhill skiers. They’re like, “I’m the best.” They’re doing something death-defying. If they don’t think that, they can’t do their sport. I always was like, “I get why they’re like that. It’s awesome.”

That’s amazing. I’d never made that connection. It’s funny, I write about this in the book, but this friend of mine is a young Olympic hopeful, team sport, and a big fan of yours. In fact, we talk about you every summer when I see her. She’s in a water sport. She’s incredibly strong and powerful. Her parents are swimmers and college athletes, not at her level. She takes a lot of comfort in you in terms of how to show up in the world. She talks about this training that they get of always bringing it back to the team. When you’re interviewed for the media, it’s never about your glory, bring it back to the team. She didn’t know. I don’t know. Is that what they say to men?

I’m going to say that as a person who’s been in a team sport, Tom Brady will say, “We.” I love Aaron and he’s a friend of mine and sometimes he says, “I.” We do want to hear from our team sports, “We,” because it is always a team effort. You could maybe take accountability if you said, “I could have done better.” I’m sure they don’t tell guys that but the ones who are more sensitive to the team dynamic, especially if you get to be the shiny stone on the team, it’s a good idea to make it we.

You get guys who’ve got their face in the dirt on your behalf to protect you so you could do your job. They get no glory. We is a good idea if that makes sense. The thing is there are many nuanced lanes in this of when it is time to break free and be like, “It’s me.” It’s then a time to be like, “Thank goodness.” Even the notion of gifts, to do something. Humility is an interesting thing because not at the point of, “No attention.” Maybe thinking that we’re a portal for talent or a gift versus, “I did something.” That’s an interesting idea.

[bctt tweet=”We have no cultural tolerance for angry women.”]

I love that idea. You’re friends with Rick Rubin. I love Rick. To me, that’s his thing, it’s different, and it’s not athletics.

He is a facilitator.

It’s funny that he’s called a producer because he’s a creative and not as much of a producer. It doesn’t matter what the vehicle is but if you’re open to it, it will come through you, and how different that is than, “It’s all me.”

Let’s say someone’s wildly successful. There’s some good fortune that has come into that and you might be smart and you might be talented and good at your job. Lucky you. It’s this weird nuance. Team sport is tricky. It’s harder for us to have bravado. You talk about this in the book where, finally, there’s a girl and she’s on the team and she’s willing to stand out and be like, “I’m the one.” Yet, the moms on the sideline are like, “Who does she think she is?”

It’s interesting because it’s like when we dress and do makeup for how it makes us feel but are we signaling to men? Are we competing with other women? Also, within here, how are we, females, also tough on each other? I always say that playing volleyball and modeling taught me there are a lot of badass girls out there. They’re big, strong, smart, and beautiful. You better celebrate them because if you don’t, you’re going to be tortured your whole life.

Let’s add other things, people more successful than you, and people younger than you. It’s celebrating young women who are killing it. That then changes and becomes defined in many different ways as we go through life. We are tough on each other. I’m curious, from your point of view, are we taught because that’s not the social norm or is there something about that? Is that a competition thing among us? I’m always curious about that too.

It’s complex and intense and hard to face that this lives in us but the social science supports it. Women are as hard on other women as men and often harder, unfortunately. Sometimes you’ll hear women saying, “I expect more from her.” That’s not what’s happening.” In a way, the sins crash into each other and there are all these Venn diagrams. I write about envy as the gateway to the other sins because envy is how we locate and identify our own wanting. Many of us are disconnected from this wanting. We don’t even know how to feel it, understand it, diagnose it, or go after it.

What happens when women in the world are doing things that we want for ourselves, our instinct because it’s in the shadow and it’s suppressed and we don’t know what’s striving us is to slap her down, “I don’t like her. How dare she? Who does she think she is?” We’ve all said these things. It’s so shameful particularly because we like to think of ourselves as lovers of women and supporters of women but it is deep. When I first wrote this chapter, my editor was like, “I don’t like this. I don’t agree.”

Is it a woman?

It’s a woman.

Girls don’t like it when it gets close to the vest though.

I said, “I’m going to convince you over time. I’ll make it last and I’ll convince you.” It’s now second. The minute she allowed herself to study and identify it, then she could find it everywhere. A friend of mine, when I was in the middle of writing this chapter, I was at a play date with her with our sons, and her mom was there. I was talking to her about envy and my friend was like, “I don’t have that.” Her mom was like, “You’ve outgrown that. You guys don’t have that.” I was like, “It’s alive in you, I promise. Think about the women who drive you crazy and you don’t know why.”

The next morning I was having coffee with a friend and I look at my phone, I have eighteen text messages, and it was this friend of mine. It was all creatively expressed moms. It was like, “Jenni Kayne drives me crazy.” It was all these women with brands because my friend wants to create a brand. It was funny and she was being funny about it but I was like, “There you go. This is what you want. You want this. It’s clear. Go do the thing that you want.”

What’s powerful about envy is that when we flip it and we start to notice who’s pushing on a dream that we have for ourselves, then we can use it. It’s the most valuable information on a soul level about what we’re supposed to be doing with our lives. You’ll notice there are a lot of women who you don’t pay attention. I don’t want to be a singer. Taylor Swift seems great, “Go, Taylor.” I don’t want to be an actress. I don’t want to be a professional tennis player.

These are badass women or it could even be irritating women but somehow they don’t bug you. I thought that this was such an important point too. Besides that, it’s an exit sign to something great, which is like, “Maybe you want that. You should investigate that. It was also taking the shame away from envy, which was, “Okay,” and anyway use it as a tool instead of, “You shouldn’t feel that way.” That’s telling you something.

I’ve read this in many books, if somebody says something to you and you get upset, you might want to take a look at it because maybe it’s too much the truth and that’s why you’re upset. Someone said to me, “You’re a selfish, inconsiderate, and short person.” I’m probably not those things but if they were like, “You don’t let your emotions out as much,” I’d be like, “What do you mean?” Maybe that’s too close to the things I’m trying to navigate. That’s a beautiful way that you couch it, which is about denying your own wanting. Rather than being upset, be like, “She’s getting under my skin, I wonder why.” It’s taking a look at that.

You’ll find there are some women who drive us crazy for good reason. I’m not suggesting that you look at someone who’s pushing hate onto the world and you’re like, “I’m envious.”

I know what you’re saying. It’s that deep chord where they throw you a little.

You’re like, “I don’t know why but she bugs me.”

“She’s doing something I want to be doing.” It’s an interesting thing. I know the difference when I’m provoked by women who I find manipulative because I don’t love that and that’s an indication to move away versus you almost can’t stop looking at the woman that you’re envious of. You’re like, “What’s she doing now?” It’s great. You go through this, you have this break, and you go, “I can’t do this anymore.” I am fascinated. You said, “All these seven sins intersect and live within all of us.” How did you come up with the idea? It’s organized beautifully around these traits. I won’t call them sins anymore.

Human instincts.

Did you have a divine moment? Were you sitting there? Did it come to you? How did it arrive?

It started with a conversation with Lori Gottlieb about envy. It’s a small moment in her book where she says that she tells clients to pay attention to it, to pay attention to their envy. That hit for me. I had spent a lot of time trying to understand what it is and why women had struggled to get onsite with other women. That had been a point in my mind, like, “What isn’t in us? What is this internalized misogyny? Why are we so hard on each other?”

For a while, I was not fixated on envy but thinking about it a lot and observing it in myself. I had a conversation with Glennon Doyle and I asked her about envy and Lori’s insight and she said, “Effectively, we don’t know what we want. We’ve been conditioned to not have any wants at all.” This was January 2020 before Untamed came out. That’s another comment that sat in my head.

Elise Loehnen – Men have as much, if not more, sadness than women. Many of them cannot locate it in their bodies, cannot feel it, and cannot process it.

I got on the plane that night after I left Glennon. Only shortly before this had I even acknowledged that I wanted to write a book and that I didn’t know what I wanted to do. It needed to be a question that I wanted to answer and spend years of my life thinking through. On the plane, I was like, “Is my book about envy? Is this it?” I was like, “This is part of it but it’s not the whole thing.”

I’m a word nerd and I started googling on the plane, like, “Where does envy come from? What’s its etymology?” I realized it was one of those sins. I pulled them up, I had to remind myself of what they were, sloth, pride, envy, gluttony, greed, lust, and anger. I just sat there, I was floored. Sometimes the things that are so obvious are also incredibly invisible to us. At that moment, I saw this punch card of goodness that could live in me, even though I did not grow up in a religious house at all and I had progressive feminist parents.

To me, it came up, this net, and I was like, “I see this. I see this structure of goodness. I see how women are conditioned for goodness. I see how men are conditioned for power and how that is tearing us apart.” To go to what you were saying at the beginning about this idea of these masculine and feminine qualities not being gendered. The way that women are undercover, incredibly balanced, comfortable, and masculine.

Most of the women I know are spending a lot of their days directing, ordering, and making things happen whether they work outside of the home or inside of the home or both. Men, meanwhile, have never been allowed culturally to let their feminine come up and that’s destroying men and it’s destroying our culture too.

I have a weird question and you’re the perfect person I can ask. I’m 6’3”, I’m 180, and I’ve been doing creatin, hydrating my cells but gaining weight. The building is burning, you’re on top of the roof, do you want me to come up and get you or do you want Laird to come up and get you?

That’s a great question.

I have the good fortune of living with a primal male who has protected this house from a fire, who I’ve seen save things, and do whatever. When I’m having these honest internal things with myself about my own biases, I’m like, “This is happening. Do I want Marianne to come to get me?” Is it a well-trained fireperson is the question. I’m saying that sometimes in these weird little tiny little moments, it’s like, “The fire is coming. I’m taking my kids and I’m going.” Laird is like, “I’m going to go up to the house.” I’m like, “Great. Have at it.”

Is it our training? Is it our environment? Someone who spent time doing something and I’ve done something else. We don’t live this way so much anymore but it is like when I think about the military. For example, I don’t even want to see. I don’t like to watch people get hurt. Boxing or gnarly football tackle, I don’t like it. I like it even less when it’s a woman. It bothers me on a deeper level. I wonder where that comes from.

I’m still thinking about who I want to rescue me. I’d want to survive in the wilderness with you. I know that’s not the question.

You wouldn’t. Not in my house. I could plan and dictate and be like this but no. You want stuff built and cut down and lifted.

A lot of it gets into this culture and nature question. With our nature, there is more of a Venn diagram around things. It’s funny because I’m married to a guy who is not that. I’m trying to think of whether you’d want to be rescued by me or my husband on the roof.

That’s maybe an interesting question. This is what I mean when we’re defining these weird, nuanced spaces of protection or something bad is happening. In a way, I’m throwing that in there because this is a safe person to have this conversation with. What I’m saying is getting in touch with a little bit of these things. I can also tell you having played women’s athletics or high-level athletics, I believe that women who compete physically at a high level have a much greater understanding of the difference because we’re right there next door and we can see the difference.

The two sharp ends of the stick, you realize they’re different. Not one is better than the other. Is it different? It is. I was always comfortable with, like, “It’s different.” It’s not less than, it’s not as important, but can I jump as high? Not really. If we say, “We’re going to move weight,” can we? Are there people who intersect? Yeah. There was a part of me that was like, “No problem. I don’t care.” It’s also knowing your own power and being like, “Cool.”

Maybe I’d choose Laird in a fire but you’re married to someone who defended your house during the Malibu fire. It’s such an extreme example whereas I choose you over my husband. You’re stronger than my husband.

Maybe not though. If Justin decided to punch me in the face or your husband in the face, your husband might be able to take it better. I try to live in a movement world and in a real way. There’s a part where I’m like, “Whatever. By the way, I don’t care.” Meaning it doesn’t threaten or press on me as a sovereign person who can do things or accomplish things.

Maybe the other part of the conversation is how we get into our own power enough that we don’t mind if either she’s a badass or certain groups of men seem collectively to probably be a little stronger in their upper body. What do I care? Sometimes when I see groups of women that have never even stood on the edge of that ledge, we’re the same. We’re all important, all of us. There are certain things like maybe we’re different. The thing you’re identifying and saying is, “Why would I feel bad as a sloth?” I don’t want to be as energetic as some of these guys around me running around or it’s okay for me to rest.

Every person and certainly every mom has had those nights where you go, “Seriously, I’m done.” You run out and you go to your room and you only do it a couple of times a year but everyone is like, “What happened to them?” You tap out and we don’t apologize for it. Maybe also within this, which I appreciate, when you get into all of your own power, the rest almost doesn’t matter.

There is flexibility or durability when you’re capable of living in your full spectrum, that’s our birthright, and that ability to move. For someone like Laird to be a prototypical, primal man, and in his masculine.

Also, drive one of my daughters to school every morning because it’s his time. I go, “I can go.” He’s like, “I only have a few shots at this.” When I read your book, I thought, “This might empower people and females so that they would get more of that flexibility and durability.” You are operating from such an interesting place where you can elevate everybody around you and simultaneously, you can be like, “Eff off. No problem.” There’s a lovingness and a harshness that gets born out of these traits when we get to peace with them instead of floating through the middle.

We’re clinging to one side out of fear of the other in this way that we’ve been cultured to be a woman, be caring, and nurturing all the time. Men conversely need to be in their masculine all the time. That is exhausting.

It’s ridiculous. Plus, those women that are nurturing all the time, deep inside, want to kill somebody. They have the heavier of the extreme because they don’t let it out.

[bctt tweet=”I write about envy as the gateway to the other sins because envy is how we locate and identify our own wanting.”]

You are full of resentment.The way that women are told to be good women, good mothers, these are sort of the social structures or parameters or this is what it looks like to perform that role publicly and ritually. I don’t think that that aligns with who we are. The same with men. I can’t speak as much of that experience because I’m not one. There is a certain balance in all of us, regardless of our gender.There are gender differences and physical differences. Where we bristle or where we get confined is when there are these ideas about how a woman should behave and how a man should behave. The reality is we’re far more interesting than that.

We talked a little bit about sloth, which we’re supposed to go until the wheels come off and be tireless for everybody all the time. Did you develop any new practices to give yourself permission to be like,

“Mom is kicking back,” how did you incorporate that?

It’s hard. It’s ongoing work. I have two boys. I certainly participate in the self-policing around my parenting. I get completely out of joint about the way that my husband is venerated publicly for his parenting. Good dads are equivalent to adequate moms.

Show up and be there, “Amazing.”

“He does drop off twice a week?” It’s like, “Let me find him a trophy.” It’s all extra credit for the dad still culturally and he benefits from that. He is a great dad. It’s still not equitable. I’ve become more clear about what I need from him, like, “I need you to do these things. Here’s an actual list.” What I’ve needed to do is to stop and it’s hard to not step in. Not to take us on a tangent but it was so present to me. Over a year ago, I fell off a horse and broke my neck. I didn’t know my neck was broken for a week.

In that week, we were in Montana, and I was packing. It was crazy in retrospect and I was in a lot of pain but I was insisting that I still run mission control and take care of everything. My husband was like, “Chill.” We got home and normally, I’m the person who unpacks and does laundry immediately after we get inside the house. I sat on a couch with my kids because I couldn’t move and stared at the bags and criticized myself, I was present in me, like, “You should get up and deal with that.” Lo and behold, my husband did. I didn’t ask him. I didn’t say anything. He unpacked and did laundry.

It was an excellent experience for me to be present with myself as these feelings were coming up. Of course, when I found out a few days later when I finally went to the doctor that I had a broken neck, I was grounded. I had a whole month to be present with myself. It wasn’t that anyone else was telling me that I should be down on my hands and knees buffing the floor, it was my own programming and that’s what became all of the judgment, like, “That’s not a nutritious dinner.”

I wouldn’t do it that way. The counter is wiped but I see some streaks over there. The other thing is, how would we relinquish control? Men are, in some ways, better at that overall. It’s like, “Do you want to fold the t-shirt with the thing in or under?”

A lot of learned helplessness too.

That’s maybe true. Also, the specific way and being what we think is indispensable. It’s like, “I can do everything and you all will need me.” There’s also this other thing that we’re trying to do, which we all try to do in all ways. You could say that at work. It’s almost like if you weren’t there, everything is still going to run okay. That’s an interesting thing to get a relationship with. It’s like, “I enhance the situation but maybe I’m not the end all be all pinnacle to all things.” With our family, it’s one other level. I don’t even use the word lazy. How about you needed to take a break? You went and broke your neck to do that.

I had to break my neck.

“I broke my neck. I’m breaking my neck here.”

My friend was like, “You’re a broken robot. This is broken robot syndrome as you sit there and trying to still do stuff.” It’s wild. It’s strong in me.

That’s also, what I would think, tribal contribution and tribal value.

It’s possible.

It’s like, “I contribute to the tribe.” Pride is the worst of all, supposedly. This one was interesting for me because you talk about the pride of our own talents or it’s supposedly the worst offense. We talked about judging women. If someone is reading this, male or female, because maybe you have a daughter, your wife, sister, or something. That humility piece is important. I don’t know where it comes from. It is teaching, like, “I’m the best.” They also take that from each other better.

Can you imagine if I came up and chest pumped you and be like, “I got you,” or whatever? You’d be like, “Back off.” What’s the conversation around believing in yourself enough so you can go for it? Be comfortable if you stand out. It’s weird because it’s a weird energy. To go for anything, you have to almost be like, “I’m the best,” or, “I can do this,” and then switch on a dime and be like, “I’m also grateful I get to.”

I think about it. The reason that it was considered the head vice or the most pernicious is that it meant that you didn’t feel you needed God. That was why it was such a sin. When you think about the etymology of humble, it’s hummus, it’s from the soil, and it’s to be rooted, which is a beautiful idea. It’s different than modesty, particularly false modesty where we’re deprecating ourselves, which is an instinct that I understand because you don’t want to inspire people’s envy by thinking that you’re all that.

For anyone who is using their gifts in the world, it goes to our conversation earlier about creativity, most of us are channeling something. There’s some universal force, you can call it God, nature, the divine, or whatever feels comfortable to you, flow. When we are doing what we’re supposed to be doing, what we’re built to do, and we’re differently abled, we’re differently equipped. What you want is different than what I want. Your gifts are different than mine, which I always think is also reassuring when you think about all of our problems and then you read in the paper about nuclear physicists who are going to solve our energy issues, etc. It’s reassuring. We were all differently gifted.

Pride, there is a certain requirement, particularly at this strange moment and time that we use our gifts in the world and that we show up and that it is that humility, knowing who you are, being rooted, and bringing it down from the vertical and spilling it into the horizontal. There is an imperative that we all show up. In that way, while pride was the head vice or the one that’s the worst, it’s the most important but it’s not the inverse but it is this idea of taking what you have and using it and employing it for other people, yourself, and your family. Be of service. Share your gifts.

Those reframes, particularly for women, are helpful. It’s like, “How can I be of service? Who can I inspire? Who can I help? Who can model their life after mine?” That is the support that many of us need. Also, it goes back to this idea of envy and stopping that behavior in ourselves and showing younger women, like, “It’s okay to shine. We have got your back. We are not going to chop you off at the knees. We’re not going to let anyone else do that either.” As we start collectively interrupting that story, it makes it a lot safer for girls and women to shine.

The other part of that would be when you’re busy doing your thing, you don’t have time to be unhappy about other girls’ success because you’re doing your thing. You could be there writing your book with your name on it and watching some other girl singing her lungs out and being like, “I celebrate her too.” The other part is when we don’t do these things and when we don’t get in touch with this, it’s going to be hard to celebrate anything, including our partner’s success.

Elise Loehnen – We’re clinging to one side out of fear of the other. We’ve been cultured to be a woman, be caring, and nurturing all the time. Men conversely need to be in their masculine all the time. That is exhausting.

What if you don’t come to terms with this and you have a partner who all of a sudden, something great happens to them and you’re like, “Yay. Good for you.” You feel threatened by that success. There was something in your book that was important and I was like, “This is amazing.” You talked about moms being a springboard, especially for daughters. It’s an interesting thing. I was like, “I understand that so well.”

Forgive me if I botched it at all. You used an analogy of a woman that you knew who was a successful broadcaster. when she was down and trying to get it going, because it’s hard, the mom was there, and they talk on the phone, “You can do it. You’re going to do it.” Eventually, she does. No matter what parenting, there’s a level of sacrifice if you’re trying to do it. There might be parents who are like, “I didn’t skip a beat.” I’m like, “I’m sure the collateral damage on that might be different.”

Let’s say there is a notion of service. As a mother myself, who has enough selfishness, still, I’ve thought about it. I’m like, “I’ve given up stuff for Laird. I’ve given up stuff to prop him up or to be here for my girls.” Also, I understood that that’s what I wanted to do. At that moment, that decision of pursuit and being available and the luxury to be available, I would like to say that.

If I’m a single mom, I don’t have that. Do you know what you’re doing? You’re providing for your family. Hierarchy of needs, there’s no conversation around it, you’re doing it. It’s great. That’s the thing. Let’s say in this opportunity, I could say, “I could pull back sometimes on work and be here more for the girls.” I was like, “That’s right.” I’ve thought about it, “I am a springboard for these girls. I want to look at that and be okay with that.”

This is big. I don’t know about your relationship with your mom but for me and my mom, my mom was born in 1950 and she came of age during second-wave feminism and women’s liberation. It’s that idea that you could be something in the world. She grew up in scarcity and lack and oldest of seven kids. Security was her. All she saw was scarcity and the need for security. That’s how she lived her life.

It’s that Carl Jung, “Nothing is more present than the unlived life of the parent.” Her unlived life has ricocheted in mine and the way that she used her own talent and ambition as the pie to my own success. She gave me everything that she didn’t have. We talk about that somewhat in culture but I don’t think that women have internalized what that means and how heavy that is as a burden.

If you choose to do things differently than your mom, you’re somehow suggesting that she made choices that you wouldn’t make or her choices weren’t as good as yours. It’s somehow an indictment and yet, the way that society is structured, the way that so much pressure continues to be on women, to be the primary parent, which I would like to see change so that it’s co-equal and more balanced, there is a lot of sacrifice for women. You don’t see men who are like, “I couldn’t go for it.”

This brings me to the other part of this. When my girls were little, you say, “Gabby, the truck is coming. They’re going to back it up. They’re dumping it. You’re the CEO now.” You’ll be on the road 10 days, 12 days a month, and long hours. Do you want it? I wouldn’t have. That time for me, personally, that’s not for everybody. Me who thought I would be more cutthroat and I had this luxury, I didn’t care about that job, whatever that job was, at all costs, without that short time when they’re little. I feel like kids are babies till they’re 3. Intuitively, it felt like, “Okay.”

There’s an interesting thing where do men not have that? Obviously, there are some obvious things about why I needed to be the one at home when they were first born as far as providing and things like that for them. There was the other thing. I look at it and I go, “I wouldn’t have wanted that.” There’s going to be other women who are like, “Yes, I want to go.” They should have that freedom. Not one is better than the other. It is to know that you can do it but to be honest with yourself about what you want.

Socially, what we desperately need is to separate this idea of loving your children with wanting to be a loving mother.

I didn’t say that. I don’t want to confuse that.

In our culture, they’re conflated.

I barely like to even play with my kids. I’m kidding. I want to do a great job but I want to live my life too. I love them but something inside of me, at that time when they were really little, whatever it was, I had the drive to be there. It wasn’t to be there and be like, “I love every minute of this.” I’m not BS with that. It was hard. I have friends, we joke, and it’s like, “Your bed smells like a manger. It’s like pee milk.” We used to joke about that. For whatever reason, I was like, “I need to be here.”

I used to joke that Laird would come and take them or whatever and you’d go, “I’m going to drive out.” You get halfway down the road and you’re like, “I should probably get back soon.” It’s like, “Are you serious right now?” I’m not talking about, “This is amazing.” When I see women in interviews, let’s say she’s a starlet, and they ask her, “How are your children?” “They’re so perfect.” It’s like, “Do you have children?” It’d be like asking my children, “Is your mom the coolest person ever?” They’d be like, “No, it’s my mother.”

Maybe later, some of them, as they’ve gotten older, they’re like, “You’re not so bad.” It’s this natural push tension. That’s why when I see women who are doing this supermom thing with every little perfect everything, I’m like, “Now you’re making it even more complicated. You have to get this sippy cup and that perfect ergonomic thing and that stroller and you go to that class.” It’s like, “It’s already complicated enough.”

There is something in our culture that drives the ritual performance of that in a way where it’s like, “I have to be good enough. I have to be a good mother.” It’s this needing to perform the duty. Whereas men have always had a lot more latitude to be like, “I love my kids and I love doing stuff with them.I have this whole life.” We don’t have these expectations around how they’re going to show up as dads in the same way that we have this default assumption about women. What I hope for all of us is that we all get that freedom to define it for ourselves.

What you’re saying to me is important because then that’s the real secret. How does your life reflect who you are and your family dynamic, your relationships, and your job? If we could get that somehow measuring up and then you go, “This is my life.” Maybe that’s it. Now with the internet and social media, I feel like they have more pressure on them to do the theater of living, “Look at my outfit, it’s cute. I’m this shape. Now we go on this trip and we do this.”

Pull out of all that and ask yourself what’s going to make you feel good. It’s hard to do it. By the way, it might even change from time to time. When my kids are little, I’m like, “Yeah.” Now that they’re older, I’m like, “I want to go deep into work.” I joke, with my family, it’s like, “Who?” Laird is going to be like, “Wait a second.” We’re over 27 years in and he’s like, “You like to make dinner.” It’s like, “I did. Now, maybe not.” It could be the moving target because of seasons and times.

That’s important. It’s essential that we unhook from all of this programming about what it’s supposed to look like and how we’re supposed to do it and do that self-definition and start both projecting new ideas about what this looks like while also stopping some of the other insanity that is ratcheting up the pressure on women.

Big time.

The performed authenticity, which also, in some ways, makes it worse. I get it. It’s not that people shouldn’t share about their lives but there is a little bit of a lack of self-examination before we project it out.

[bctt tweet=”In our patriarchal culture, sadness does have this feminine quality. To be sad is to be weak.”]

Gluttony. It’s funny. I am not sure. Because of my size, you’re a little big girl too, but I pulled out all that. I was like, “I’m never going to be the same size as anyone else.” Of course, I do the usual, like, “Cellulite, they’ll wrinkle,” whatever. This is interesting for me because I hear gluttony or dealing with our own hunger. Why do we judge ourselves or others? Were you able to break this?

It’s hard. The same with you, I am tall and I’m not small. I’m not a bird.

That’s great.

I’m strong and I am grateful for my body and what it can do. Similar to you, I live on this edge. If I keep myself, and I have done this in my life, underfed, I can live in this world of thinness and slenderness and make myself smaller and more diminutive. I have been bucking against that pretty wildly in the last few years because I‘m tired of using my emotional and mental energy to chastise myself. Part of doing this work was this recognition, “I am disconnected from my own hunger. I eat on autopilot.”

What do you mean eat when you absolutely have to or you didn’t tap into, “What do I feel like eating? Is it time for me to eat?”

I was eating very fast, standing over the kitchen sink, not enjoying what I was eating, and already chastising myself for eating one piece of pizza as I would reach for another but not like, “This is fun. This is delicious.” I have these little boys and my husband probably weighs less than I do. I don’t weigh myself anymore.

I have a friend who told me a story. I didn’t know this was a thing. She goes, “I go to the doctor and I won’t get on the scale.” They’re like, “You have to get on the scale.” She’s like, “I’m not getting on the scale.” She goes, “If there’s a problem, you’ll let me know.” I was like, “Is that a thing?” She goes, “Yeah.” I go, “Who cares? It’s a number.” I was trained differently. I know girls that are 200 pounds and are strong and powerful. I never equated it to a thing, like, “I have to be 120. I have to be one 130. I have to be a size 4.” It’s like, “Are you serious?” That’s a real thing. It’s weird to me.

There’s this idea, this fixation on the weight metric as indicative of all things, which is insidious because you can weigh nothing and be pre-diabetic and you similarly can be big and be incredibly healthy. Fat is health protective, particularly when it’s subcutaneous. You don’t want it wrapped around your organs but you can be thin and have visceral fat in your organs.

We call it skinny fat.

As a child, I had congenitally high cholesterol. Do you have the same thing?

Brutal.

I haven’t looked in a while but I’m sure I’m at 230 or something.

I’m higher than that. By the way, there’s no correlation to cholesterol and heart disease. It’s like, “Who cares?”

When I was a kid and they did my labs and I was swimming ten hours a week. A slip of a kid. My dad is a doctor and my mom is a nurse. At that time, they sent me to a nutritionist and put me and my older brother on a low-fat diet. At that moment, for me, there was a powerful disconnect where I was like, “I know that I am healthy.” My labs are disconnected.

It was an important understanding for me at that age when I knew, at that moment, that everything that numbers said about you wasn’t necessarily accurate if that makes sense, which has helped me, at this point in my life, push against all the moralizing that we do about body size, virtuosity, having your body under control, and being as small as humanly possible is the signal of goodness and desirability. For anyone who’s reading, you might be alone in this but the dysmorphia that has chased me throughout my life. When I look back at pictures of myself in high school, I was a rower. I had a slamming body.

You didn’t get to enjoy that.

In high school, I didn’t have an eating disorder but I went to boarding school. They’re contagious. It was the first time when I was like, “This person says that she has a bad body and she’s smaller than I am. What am I?” The contagious of this. I look at myself in my 20s and 30s and I’m like, “I looked good. Can I allow myself some grace now and assume I look much better than the mental picture?”

How about you do that forever? When you’re 85 and 90 and you look back on this exact moment, you’re going to be like, “I was fresh-faced.” It’s a constant practice for all of us to be like, “I understand this human thing I’m experiencing but it’s not going to land. I’m going to let it roll. I’m going to keep trying to appreciate what it is right now.” Spending your whole time being tortured about what it is, it’s no way to live. I understand the transition of puberty, that’s just a weird time. Let’s say that time, we get it. After that, it’s like, “Be robust. Be whatever you are.”

Particularly because life is hard. I think about aging and I look at some of my friends who are thin and I think I need some fat. I want to age with fat on my face.

Do they look happier?

No.

That’s the other thing too. You look in the eyeball and you go, “Fun, vitality, and playfulness, that stuff is for me.” It’s not like, “I’m a two. I’m a zero. My bag matches my shoes. It’s amazing.” It’s like, “Okay. Is that great? That’s great.” I see a lot of that and you go, “Okay. Anyway.” For girls, it’s not teaching them to be playful and be rowdy a little. I don’t mean girls gone wild, I mean have a little fun. Have fun with yourself and have fun with your girlfriends. It’s okay to be playful and even inappropriate in that masculine way. Sports help with that.

A big one is lust and desire. I can relate to this. For girls, I feel like we react 1 of 2 ways if we’ve either had a sexual situation or we just are bucking it. Either we’re far in one way or we don’t know how to say, “These are my needs and wants.” It’s an interesting one, sexuality and lust, and people saying words where it’s appropriate. In certain ways, it is places where it’s appropriate. If I’m reading a bedtime story to my kid, office, no, and in your bedroom with somebody, yeah. How do you get in touch with it? How do you feel good about it?

For women too and going back to this whole theme of wanting and desire, many of us were never taught how to connect to ourselves as sexual beings. We rush right to the performance of it culturally, right to sexiness, right to the objectification of ourselves, and in the eyes of others even if we have no idea what we like. We don’t know how our bodies work. We have no blueprint or template for what turns us on. We don’t know how to communicate that to a partner. That engine in us isn’t running.

I write about this developmental psychologist, Professor Deborah Tolman, and her whole thesis is that girls are taught to be desirable but never desiring. That’s our culture in a nutshell. We’re uncomfortable with women who are the drivers of their own sexuality. We much prefer this passive sexy idea, this place for projection of fantasy rather than women who are like, “I want to be touched like this. I want it like this,” etc. That’s still new to us and there’s a lot of shame around that.

We send out our girls. It’s hard because you get into this space, you have three girls, where you feel Puritan and there’s this whole, “Don’t be a sledgehammer. Don’t be a body shamer.” It goes to this, like, “You’re very sexy. Are you sexual? Do you know what that means?” There’s also obviously a big disconnect between where a lot of our empowered girls are and where culture is. We still live in a culture that makes girls responsible for whatever any boy or man does to them. Unfortunately, that is where we’re at. It’s not safe.

It’s interesting though too because you said desirable versus desiring but yet, in weird ways, culturally, we’ve magnified the desirable. For me, I’m like, “Whoa.” I feel like we have never objectified ourselves because we have new signaling. We’re trying to penetrate the telephone. Now, the lips are bigger, the boobs are bigger, and the eyelashes are bigger. We’re trying to create attention and the most magnified way I’ve seen at least in a while and yet, it’s like, “Is that for you? Who is that for?” If it’s for you, great.

The two don’t go together necessarily.

The one is quite a lot of work, by the way. To put it together like that is a lot of work and to have the time to try to figure out what you like and want and to be able to articulate that.

Elise Loehnen – Women’s anger is essential and typically righteous and needs to be understood, channeled, and properly moved. Anger turned inward is killing us.

To be in your body. I think about someone like Kim Kardashian, who I don’t know. No shade on everything she’s accomplished but she’s obviously a hypersexualized person in our media. She exemplifies sexy, I would say. She doesn’t strike me as very sexual. I don’t look at her and think, “She’s deeply erotic feeling herself in her body.”

Helen Mirren seems more sexual to me than Kim Kardashian. I don’t know why she came to my mind.

Cate Blanchette. There’s a real difference.

Do you think if you knew one, you would need less of the other?

Yeah. Sexuality is deeply personal. To me, it’s the source of our creative power, it’s what runs up and down our bodies and it’s very much attached to our pelvic floor. It’s our whole receptor of the world. The two have nothing to do with each other. You can meet a deeply sexual woman where you’re like, “There’s something magnetizing about her. She feels powerful and embodied.” She might be 80. She might be wearing a flannel shirt and Dickies.

You got to watch out for those ladies. I have a daughter, and I won’t say which one, who I realized was way more provocative naturally. I was like, “Interesting. How are we going to help guide her to her voice because her own sexuality was more dynamic or nuanced or something than me?” I thought, “It’s going to be so interesting to try to figure out how she figures it out.”

It’s scary too as another woman who’s the mother. I don’t care what anyone tells me. You still want to protect the bits. You have an instinct. Part of you gets to a point where you’re like, “As long as you’re in situations you want to be in, that’s all I can hope for you.” You realize, “I’m out of my depth. She’s going to grow up speaking a language I didn’t do quite as much.” It’s always interesting. Why do we make it dirty?

That’s all Augustine. That’s the 4th century. That’s not Jesus stuff. That comes much later, this idea of celibacy, and women as sinful agents. Augustine, in the 4th century, was the one that turned original sin, which isn’t a thing in the Bible, into a less driven action where Eve incited lust and caused the fall. It’s completely dislocated and disconnected us, women in particular, from our sexuality, and probably men too. Men are simpler.

You think? I say that with no smoke at all. By the way, one of the other meanings of Eve is beneficial adversary or helpful adversary because people go, “How come you think you and Laird stay in a marriage?” He jokes and he’s like, “It’s like the Cold War, we circle around like this. In the military, it’s agreed mutual destruction.” When I heard that the meaning of eve is beneficial adversary, that was amazing. It’s like, “I’ll help you.” “No.” You push against. I was like, “That’s an interesting meaning.”

A source of polarization, which is important.

It’s fantastic.

Any sexually dynamic relationship.

You got to keep that rolling. I’m scared and excited.

You can’t be too friendly.

I don’t want to be that. I have friends. I love him. I want to be a little like, “What’s he going to do?” That’s just me though. A big one is anger. Anger is interesting. I’ve used anger a lot in my life and felt less apologetic for it. I’ve tried to use it less. It was covering some fear responses for me. That’s how I would deal with being fearful, I would lean into it with anger. I believe it is such an important and powerful and mobilizing emotion. We trip out when girls get angry.

It goes back to like fear of the goddess, all these destructive goddesses. Men are terrified of angry women for a good reason.

They want to go, like, “Do you have your period? Is that the time of the month?” It’s like, “No, I’m just pissed.”

We have no cultural tolerance for angry women. Women’s anger is essential and typically righteous and needs to be understood, channeled, and properly moved. Anger turned inward is killing us. As you said, anger is often a secondary emotion to fear, shame, and grief. When we can’t process our anger, we can’t access even those even deeper emotions, which we need to move. Anger is how we establish what we need and where the lines are that have been crossed. It’s all of our boundary work. When we run it over or suppress it, nobody wins.

You can see a man and he gets angry and somehow it’s not personal. Do you ever see it? It calls him to action and he does it and it’s over. By the time we finally get angry, because now it’s personal, we’ve been pushed, and we finally have given ourselves permission to say something. That’s why we have a harder time coming back from it or not making it personal. I was thinking about this. I was like, “Could I do this better?”

Also, if I could not listen and be as sensitive to what I’m hearing. Sometimes we get offended or we take things more personally because we also, on the other side, have not given ourselves permission to sooner say, “This isn’t working for me.” Especially in the workplace, you know this because you were a boss. How do you use that tool? Sometimes you have to use it and say to people, “We’re going to have to do better here,” but then we let it go sooner.

I agree with that. Part of it is in that moment addressing the underlying need, the Marshall Rosenberg non-violent communication model of, “I am angry because I am needing.” It’s less adversarial but it is more direct. It’s kinder and clearer. People can recognize that need without feeling attacked. The thing is none of us have been taught how to have healthy conflict.

When you think about the ways that boys and girls are acculturated, boys’ aggression is completely natural and normal in children and all humans. It is part of life. For boys, it’s completely acceptable for them to be physically and verbally angry and to express their aggression that way. We get it. We don’t like it necessarily but we get it. For girls, meanwhile, no way.

This gets back into the envy conversation but it comes out as whispering gossip, alliance networks, and exclusion. We have this feeling and we need to put it somewhere. I don’t think it’s our nature. This is culture. This is how we’re taught that this goes down because nobody is teaching kids. Maybe it’s better now. It’s like, “When you’re upset with someone, this is how you handle it.” Let’s practice. Let’s coach. Let’s teach each other how to give feedback and model.

It’s become interesting though. I love to see what you think about this. Sometimes, it’s like too much talking though, culturally. I’m older than you and my kids are older. Sometimes it’s like, “Knock it off.” It’s not like, “When we do this and then we throw a break at Johnny. We don’t do that.” It’s like, “Don’t do that.” Sometimes it’s a weird thing. When we’re parenting, it’s like, “Model it. Are you upset? What’s up? Tell me.” Now we’ve also got a group, every feeling and every single thing. I’m like, “This is life. Life is hard.”

It’s interesting. I had written a fair amount about this man, Joe Newman, and I ended up taking it out for space. Have you met Joe? Do you know Joe?

I know who he is.

He wrote the book Raising Lions. He’s a fascinating guy who works with lions like disruptive children and kids who act out a lot. His point is salient for everyone, adults too, which is to stop moralizing and stop explaining. Take your child and give them a timeout, not like, “You’re being cast out from society,” but as an opportunity for them to gather themselves and collect themselves and come back. He was this kid.

[bctt tweet=”It goes back to the fear of the goddess, all these destructive goddesses. Men are terrified of angry women for a good reason.”]

His point is kids know. We all know when we’re out of control. We know when we have lost it. To be the double downing of like, “You shouldn’t do that and stop doing that, Gabby. It’s not helpful.” To be offered the grace of, “Take a minute. We can talk about it if you want but we don’t need to. Take a minute.” Letting kids start this practice of removing themselves and getting under control.

Take a breath.

They can come back in without it needing to be this whole lesson.

Thank you. I got to tell you, there are times when I’m like, “I feel old-fashioned now. I’m out of touch.” I didn’t beat my kids or anything. It’s nature to model or to let people be angry. One book I read said, “Hold on to your children as long as you can.” They talk about, “That must be tough. Tell me how you feel.” That would be hard. You have a conflict. They see you having conflicts at home. How do you deal with it?

Resolving it in front of them. I love the book, Hold On to Your Kids. You can have empathy. You can meet them at the moment without an escalation and without shaming the expression of that rage but by saying, “We will talk about this. You’re upset, I get it. Go be upset.”

What you didn’t do in this book, which I do see more of right now a little bit, it’s hard. Everything’s hard. We need a place. How do we emotionally and verbally evolve and stay wild and stay in nature? I don’t care what’s coming. I don’t care about transhumanism. We’re not there. How do we deal with hard things?

The world is hard and unfair. Nature is savage. How do we go back to developing a bigger emotional IQ, what you’re talking about in these genders, teaching girls like, “What’s up? Do you want to go for it? Let’s go for it.” Do you want to stay home? Do you want to be a working mom? You’re frustrated about something. Communicate. If you like it this way, say that, don’t feel weird, dirty, or shamed. We’re still a part of this nature. I’m always like, “How do we have all these conversations and not abandon them? We’re a part of nature.”

What you’re saying too is important in the sense of honoring our feelings, letting them come up, processing, and doing that work in part so we can show up in the world without not necessarily bringing it.There’s this idea that you have to be pissed off to go out and change the world. You’re not a furious activist. You’re an ineffective activist. That’s part of our consciousness, even if we don’t say it. You need that animating energy to take action in the world.

Not that it’s the opposite but maintaining that burns a lot of energy. The better that we get at moving how we feel, the sooner we can get into action and address the things that we want to see in the world, including the manifestation and expression of our own dreams and gifts and a more equitable world, a safer environment, a preserved environment, or whatever it is. You don’t have to be furious to go to the courthouse with Moms Demand Action. You need to, in some ways, be a well-run Ferrari.

You got to be laser-focused too. If you’re going to sustain it, you can’t be hysterical. You’ll get tired. You’ll be taking naps. Sadness is the last.

The one that was cut from the list.

How did we manage to not say it was okay to feel sad? What happens there? How does that show up?

It’s just dropped. We don’t know why it didn’t make the list. It was these eight thoughts and then it became the seven cardinal vices. The way that Evagrius Ponticus writes about sadness has a feminine soul and it’s primarily in the context of homesickness, these monks who have abandoned their families. Sadness makes people passive. In our patriarchal culture, it does have this feminine quality. To be sad is to be weak.

I wanted to include it because we’re culture-drenched in sadness and grief. The people who are most affected by this dislocation from their feelings are men. The primary symptom of this is toxic masculinity and this idea of evading death and not acknowledging that we’re part of this cycle and not acknowledging the planet. There’s more dominance, conquering, and I’m-above-it-all mentality, which is killing us and certainly killing men.

Men have as much, if not more, sadness than women. Many of them cannot locate it in their bodies, cannot feel it, and cannot process it. I wrote a lot about Terry Real, who started his career working with men. He wrote this book called I Don’t Want to Talk About It. In it, he identifies that while women are more likely to be diagnosed with overt depression, with men, when you add up the incidence of depression, personality disorders, and addiction, the two equal out. Men are far more likely to take their own lives. They are more likely to be involved in deaths of despair.