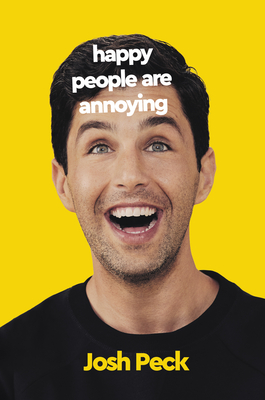

Episode #118: Josh Peck: Childhood Star, Overcoming Obesity, Drug Addiction & Learning Not to Run Away

Today, my guest is actor, comedian, child star, and now author Josh Peck. You may remember Josh as the lovable child actor from Drake and Josh. Josh has lived many lives since those years and shares his journey through growing up not knowing his dad, massive weight loss, drug, and alcohol addiction recovery, and learning how NOT to run away in his new book HAPPY PEOPLE ARE ANNOYING.

Life is about learning and moving on from challenges, and Josh opens up about how he has navigated his hurdles. His humanity and openness are a true reminder that we are not alone. The book is lovely and entertaining, just like the author. Enjoy

Listen to the episode here:

[podcast_subscribe id=”5950″]

Key Topics:

- Behind the Comedy [00:03:03]

- The Man of the House [00:08:09]

- Standing Up at Eight [00:19:04]

- Finding Relief in Food [00:27:22]

- A Version of Stillness [00:40:11]

- Eat a Little Less, Exercise a Little More [00:44:36]

- Food as a Big Obstacle [01:00:54]

- Defining You [01:04:44]

- Being a Partner [01:18:00]

- A Great Teacher [01:25:13]

- On Childhood Actors [01:39:56]

Josh Peck: Childhood Star, Overcoming Obesity, Drug Addiction & Learning Not to Run Away

My guest is actor, comedian, child star, and now author Josh Peck. We had a great conversation. I know Josh. He is a curious, fun, and soft human person. He has a book called Happy People Are Annoying, and he gets into it. He talks about feeling different, growing up without knowing his father, being overweight as a young kid, and never mind how he lost weight on TV. He didn’t get to why food became the outlet, which turned into a drug and alcohol addiction. He loses the weight, then he has to contend with an addiction, how we recovered from that.

That journey is not only heavy, but he makes it funny. He’s a dad and a husband and still looking at things. Josh goes back to acting school. He said, “I was the most successful person there and the worst actor in the class.” The conversation is inspiring, how he lost the weight, how he keeps it off, and how he has learned not to run away. When we suffer pain when we’re young, the minute it gets hard or we feel vulnerable, we run away. He shares how he lives now has helped him not do that. I love Josh. It’s a fun conversation. I hope you enjoy the show.

—

Josh Peck, we’re switching the order. You were talking to me and now I’m excited I get to talk to you.

What an honor.

Thank you for coming my way. Congratulations on your book.

Thank you. I don’t see you and Laird that much, but this kinship and to be able to share it with you and have you read it meant a lot.

I read the book. It’s titled Happy People Are Annoying, which I thought was appropriate coming from you. In that title, the thing that comes across is the pushing out weirdness of you, your funniness, your friendliness, and then the part where you’re like, “Is that okay?” You get into that duality in the book. A lot of times, people are distracted by the comedy and they don’t see what the person is going through. That’s the oldest story in the book about comedians. The pain, and then we’ll put the comedy in front. I have to ask, as somebody who has worked for a lot of years in a lot of different ways, what made you think, “I’m going to take on writing a book.”

The Advance. Huge.

Seriously? How did you get to Advance and books these days? That’s amazing.

Who doesn’t love money? No, I’m kidding.

You’ve got to stay practical. You have a family.

That helps. My son loves diapers and all these necessities. I live this incredibly public life advertently in front of the camera since I was 12. I’m part of that last generation that grew up where famous people were mysterious. They kept a guard, they kept their real-life completely sectioned off, and what they presented to the world was what they wanted people to see. Now in the new age of social media and whatnot, everything is out there for people to consume, almost to a fault.

I found that all of a sudden, I was 35, I had a wife and a son, I’d grown up. I had faced these challenges that I never quite shared with people. In order for me to make peace with my origin story and everything that I’d been through, I felt the need to be honest with my audience and say, “What got me through were people sharing their own trials and tribulations and feeling that power of me-too in perspective.” The only way that my experience will be of value is if perhaps I can help someone else through what they’re going through.

I can feel you through the whole book. It’d be a great joy to listen to the Audible because you read it. Your voice is clear in the book, like, “Reader, I thought we were friends.” I feel you in this, which I appreciate. There are so many points in this book, whether it was taking care of your health or how you managed it or finding something to escape in or dealing with your business. There are so many points that are relatable for people. Yes, you use acting as a platform to tell your story but it’s about you, the human being. You did an incredible job. I know books are hard. There’s something liberating about putting your story out there once and for all and then going, “Great. Now we’re onto the next.”

It’s such a good point that you make and that’s true. Weirdly, I’m starting to talk about the book and promoting it a bit. These stories, which had a lot of power over me from as far back as I can remember, I felt like I needed to hide my career insecurity from the world or what it felt like to be 100 pounds overweight on television at 16. There were so many moments where I felt like, “Better to just make a joke and move on.”

In facing it, you’re right, I’m able to move on. When you’re a young comedian and you’re bombing, the worst thing you can do is to not acknowledge what’s happening because all comedians bomb. It’s a part of it. It’s got to be bad at first. As you become more of a craftsman, you’re able to let the air out of the balloon in front of the audience. You can make them comfortable, like, “Welcome to a comedy show. This is the rough side of what I do. We’re on the ride together.” This is my attempt at letting the air out of the balloon and saying, “We’re all here together. I’m human. You just maybe watched me growing up.” The way to paint yourself into a corner is by acting like it never happened and completely trying to negate your origin story.

It makes me think of something you said in the book. Even though you’re in this body now for a long time, you’re still identified as the fat kid. A lot of us have a story, even though we’re not living in it anymore. We’re still dictated by those rules of engagement, whether it’s like, “My mom was mean to me,” or, “I got teased at school.” It’s like, “You’re living a successful life and that doesn’t exist anymore.”

A lot of us live in an old story. You frame it perfectly because to look at you, it’s like, “I look at you today as you are now.” You’re not the fat kid. All of us experience that. I had a friend who played football and he’s from Pennsylvania. He’s a tough guy and didn’t say I love you very much. He’s like, “I had to rework it.” He’s in a loving marriage and he has two kids that’s grown. That story’s over.

How do you heal from that? You showed this in your book. Let’s go back. I want to take a little bit of a journey through the book because there are so many things to it. The deli meeting, if you will, with your mom, your mom is wild at that. We always have these ideas about people, but sometimes people have wild things happen.

There’s nothing I love talking about more than my conception. My mom was this self-made single woman. She was born in the ‘40s when World War II wasn’t completely over yet. She truly lived through women’s lib and all the challenges that especially women face in the ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s. I always say my mom was born a couple of years too early because she missed The Beatles and hung on to Barry Manilow. Shout out to Barry Manilow and Barbra Streisand. We love them.

I’m like, “Ma, did you go to Woodstock?” She’s like, “I was 30. Am I going to be in the mud? It’s so dirty.” The story is my father and my mom were acquaintances, someone that you would see twice a year and you meet for lunch and say, “We should do this more, but we never do.” He was in his early 60s and had grown-up kids and a wife. He invited my mom over one night and they slept together. He was apparently separated.

[bctt tweet=”It’s amazing giving people the dignity of their own experience.”]

A good, old separated story.

It was a quick separation.

Just that night, they were separated.

It seems as though as soon as she got pregnant, he was suddenly back with his wife. I’m glad they worked things out. Love can prosper. There she was at 42. She wanted to always have a child but assume that maybe it wouldn’t be in her future. This is the ‘80s. I don’t know how many people were doing IVF then. Did that exist?

Probably a little bit if you had the Jing.

Early days. She made the decision she was going to have this child knowing full well that she was perhaps signing up for what would be a challenging life. There were no illusions. My father quickly walked away and said, “I’ll have nothing to do with this.” Growing up, it seemed as though to me my friends and their family were part of a closed corporation. The parents were upper management and the kids were employees, and orders would get barked down from upper management.

My mom and I were like a startup and figuring out our way. We were partners in many ways. She was certainly the mom and took care of me and protected me. I became, in an odd way, the man in her life because she couldn’t shield me from much. We had to have an agreement, a partnership because we face a lot of challenges.

This is how you survived together. You do write in the book about how you were the man. It could be even the man of the house, but it’s also in this partnership. Especially a son to a mother, that puts an interesting load on a young man because they’re protective of their moms, they want their moms to be okay, and they feel responsible for their moms. It’s a lot.

Even if it’s unintentional, you don’t see the dynamic the same in the other directions quite like a son and a mother. You talk things about making sure your mom’s okay. It’s an interesting thing because it’s beautiful that you can survive together, but then there’s something to be said for not having to worry about your parents.

There are so many different dynamics that go on with kids and their parents, if you have both, and if you have more of a “normal upbringing” where you’re not maybe acting when you’re 11 years old. There are advantages and disadvantages to all of it. My mom had to take my dad to court when I was nine months old. He gave us a bit of money and walked away forever.

I always asked her, “What was that like?” He was this guy who, for many years, she thought was this wonderful mentor and quickly became this disappointing person. She always says, “He looked at you because you were at the courthouse with me at nine months old. He touched his heart and walked away.” I don’t think my mom is purposely lying to me. Parents tend to put a halo of decency around life for their kids, especially at a young age.

The world is unjust. We learned that either early on or in our 20s and 30s. I did have a lot of love. I did have the deep, important things that are fundamental to raising a child with self-worth and feelings of security. I did have this awareness of like, “The Pecks aren’t normal. Life is not fair. At every turn, whether it was not having to dad or being overweight, or being the musical theater kid at 12 when I should have been playing T-ball, I was like, “The Pecks are different. I’m always going to be the odd man out.” It took a long time to make my peace with that.

Do you think standing here as an adult who sees a lot of different shades and areas of life that you realize that’s all a game anyway and every house and every person has their own version of feeling like, “We’re different.” Yours was more obvious. I feel like we get this weird picture. For me, it was Leave It to Beaver. My mom trained dolphins in a circus when I was two and my dad passed away when I was five. All I wanted was to Leave It to Beaver.

The magic that comes out of some of the things that are challenging, you can’t replicate. I feel like sometimes, “I’m different. I don’t fit in,” is part of the human experience. We think that we’re only one of the people going through it but on any level, whether they have two parents or not, maybe it’s a kid who’s like, “I don’t fit in with my family.” Who knows? As I’ve gotten older, I go, “A lot of people experience that. It’s just not as obvious.”

It’s an unavoidable part of growing as a human being and facing the trials and tribulations of existence and evolution. We all experience it in different ways. I talked about this in the book. I never knew my grandfather but from what my mom has told me, he was a guy who liked to eat a lot, drinks a lot, smoke ten cigars a day, and drop-dead at 50. A lot of people would hear that and be like, “That sounds awesome.” Not the dying part but everything else, I’m all in.

He then had my mom and she too had her struggles with overindulgence, food, and whatnot. She had me, so there were three generations of people who were struggling with overdoing it and the trauma that comes with that. Jewish people, especially in the northeast, of the ‘20s, ‘30s, and ‘40s, there was so much trauma going on anyway that there was this epigenetic, transgenerational passing on of that trauma.

My mom corrected to the best of her ability what her dad did to her and thus gave me a good opportunity to do even more correction. My wife is fantastic and healthy. After several years, she hasn’t proven to be a total kook yet, except for the part of loving me. I look at this kid of mine and I go, “You have a chance at only being reasonably dysfunctional.”

That’s a dream for a parent. I always tell Laird, “I can’t wait till these girls get a little older and they let us know how badly we’ve screwed it up.” You were singing Paige’s praises about how calm she is and navigates that. That’s what partnerships are also for. We’re learning not only from our experience, our children, but on certain things, our partners are going like, “I’ll take over right now and just chill out.” You’re like, “Good idea.” Just watching them.

My youngest daughter said, “Dad is always crowding me. He wants to hug me and wants to know where I am. What’s going on?” I said, “Do you know what’s funny, Brody? The only thing is that we’re only going to be seen as 1 of 2 ways. We’re either going to be on top of you or we’re going to be neglecting you.” Parents have to decide what they can deal with, so you come back and go, “I can live with that.” There’s no middle.

“You did a great balance of moving in when I needed you to and giving me space.” No kid is ever going to say that to their parents. As a parent, you start to realize it’s going to be something. Maybe that’s what propels us in life. Maybe that’s our schooling. It’s like an injury. I always say I learn everything and I make all my adjustments through being physically injured as far as my physical practice. If I always felt great, I wouldn’t do anything different. The pain is built-in to having to do it. Were you doing standup at 8?

About 8 or 9.

Josh Peck – Laughter and crying are involuntary. That’s why when people can make you laugh, it feels almost like a magic trick.

Where do you get the chutzpah to be like, “Yes, I can do it.” It’s interesting, you talk all through the book about the tough relationship between performing and doing it well, and then it being hard for you. I appreciated that. Where do you get that inner courage to be like, “I can go and do that.”

My mom was such an example because she had dealt with issues with food and weight stuff throughout most of her life. My fear that people could take away from the book or that would be the wrong way or at least it would be unfortunate if they looked at is the part of me talking about my weight. I speak in a hyperbolic way where I make fun of myself and I want to be honest that for me, weight was a real issue. It was also at a time when we didn’t have body positivity. We didn’t have what’s present today, which was wonderful and necessary.

I tried to paint in a somewhat brutal picture what was going on in my head during that time. I don’t want it to negate anything of people feeling utterly comfortable in their own skin today. I faced a certain challenge when I made that change. It’s my mom dealing with that for herself, and then also being the self-made female business person, she needed to take over rooms. Like I say about comedy, you can be a lot of things. You can be too nice and you can be too emotional, but no one’s ever too funny. No one’s like, “That Rick, I love him but he makes me laugh too much.”

It’s a magic trick and it’s visceral. Laughter and crying are involuntary. That’s why when people can make you laugh, it feels almost like a magic trick, like, “Do it again.” I watched my mom use it as her superpower forever. She’d walk into a room and say, “Everyone, look over here because the entertainment has arrived.”

I talked about this one moment in particular when I was at a Jewish holiday dinner at 8 years old. I fired out this joke that my mom had told me a couple of weeks earlier. There’s a moment in the conversation where everyone’s looking at me trying to process what happened with this 8-year-old kid telling a joke about breast enlargement. It’s a good joke. At that moment, anything could have happened. Had they not laughed, I can be an accountant in Boca right now or a Bitcoin miner in Norway. So much could have happened, but they laughed their asses off.

Immediately, I felt like the Boy King. I said, “This is of value. This is a currency.” I can summon it at 8, which is rare. There’s little adult social currency that you can grab on to at such a young age. That’s why I started acting and throwing myself full force into this thing. I had a bit of natural talent for it, which was lucky but I also was incredibly ambitious. I was this only child and the focus was on me.

My mom said, “If this is what you want to do and it gives you confidence, I’ll help support you.” That led to me reading an actor’s magazine one day when I was 9 years old. I don’t know how I got it. I found my first agent, and then looked at me and said, “I can get you five minutes of standup time if you’re willing to get up and put an act together at a local New York comedy club.”

Is this at night where they have to usher you in at the back? Is this the whole thing?

Yeah. They sneak me in so that they wouldn’t lose their liquor license. This was three times a week. I’d get home from elementary school and mom would be like, “You got to take a nap.” I’d be like, “Why?” She’d be like, “Because we’re going to be out till 11:00 PM. Take a nap now so you’re not completely crushed for school tomorrow.”

Can you give me an example of a joke as a 9-year-old? Would you be like, “As I was on the playground…”

I’d make fun of my mom and make fun of kids at school. I felt proud of this one joke that’s not good but coming out of a 9-year-old, it helps. I don’t know if you’re familiar with Entenmann’s.

Of course. I even know what Dairy Barn is. It’s a drive-thru place that had Entenmann’s and the chocolate-covered donuts, the powdered donuts.

That sounds awesome. It’s my kind of place.

You don’t have to get out of your car.

Even better. Who wants to be with people? Entenmann’s was this grocery store, baked good stuff. I would always say, “At school, I majored in Entomology, the study of Entenmann’s.” Coming out of this chubby 9-year-old, they were like, “That’s a good joke.” That became my shtick and I wound up doing it on Conan O’Brien and Rosie O’Donnell. It became my calling card.

It’s hard to read where you talk about agents saying, “You’re too big for commercials,” and that you went to the Jewish Community Center. That was where they first napalmed you. This is where they called you a name. It felt like it was one of the first times that it was like, “This is wounded.” People have those moments.

I was talking to a friend of mine who’s a giant 320-pound NFL player. He talked about being whipped for the first time at five by his dad and he’s like, “I felt betrayed.” I was like, “Oh.” Everything was good, we were having fun, it was fine, and then like, “What’s happening?” He said it had an intense impact on him. I thought it was a beautiful way of explaining it. That moment where they referred to you based on your weight, what do you do with that? Because people get that. I was tall, daddy longlegs, Jolly Green Giant, whatever.

Did you get teased a lot?

Tons but I don’t know if it’s different. I had a tall mother but I looked at it like, “Everyone is tripping out about how tall I am. I’m not tripping out how tall I am. They’re tripping out about how tall I am.” I was 6’0” at 12. I always had space for it. I made it their experience. You’re going through puberty. You’re uncomfortable. Everywhere you go, people are staring at you or say things like, “You’re tall.” It’s like, “Thanks.” I managed it. I did try to be less than. I tried to be a little smaller. The Jewish Community Center is probably a safe place.

[bctt tweet=”What are you willing to give up that stands between you and happiness?”]

Yeah. There are a lot of young Jewish jerks. I was like, “We got to bond together. Six years ago, they were running us up. Come on.” It was that moment where I said, “It’s going to be hard looking like this.” I’d always known we were different, but I had this social currency. I had this ability to win your favor, but a fellow 10-year-old is like, “I’m not impressed with you. I’m going to make a snap judgment about the way you look.” I knew from that moment on, I was like, “I’ve got my work cut out for me.”

You talk a lot about the relationship with food, the joy of food. This is where a lot of this experience was, or maybe looking for the feeling. From food, it became other things later. When I ask, this is more I’m trying to understand. What does it bring you? Is that also an isolated experience? You could share it with friends, but are you feeling like no one is understanding what’s going on? The food becomes the friend or the place of good feelings. What is the food?

For most people, food is their first foray into using something to numb whatever’s going on, whether we know it or not. It certainly is societal. It’s used as this reward system. Even more so at a young age, whether I knew it or not, I had this propensity or this proclivity for these overwhelming feelings. Especially in my household where there was a lot of financial insecurity, single mom, feeling like I was in this position. It’s from the park bench to Park Avenue. It’s from the state Penn to Penn State.

Had I been born to some rich, typical family, I don’t know the sack of dysfunction that I would have been handed from that scenario. I can only speak to my experience. I knew that food was this thing that offered me some relief. I heard it said once in a twelve-step meeting, “I wasn’t trying to kill myself. I was trying to kill the part of me that wouldn’t let me live.” That voice that woke up a few minutes before I did every morning told me all the ways I wasn’t enough.

For me, I had those feelings from as far back as I can remember, and the only thing that offered me any relief was food. I was not cognizant of it. We mirror what our parents offer us. Seeing my mom’s struggles with it, I don’t know if she presented the healthiest relationship with food to me, but what can you do? She was doing the best she could. It was for me to figure it out. It was certainly this anesthesia and it allowed me some relief. Like anything like that, it had such quick diminishing returns.

If you get sick and you have to take something exogenous like prednisone and you have to take steroids, they say, “You must do it for a brief run because the moment your body ceases in an artificial form, it’s going to stop making it naturally.” Similarly, as soon as my body saw relief, my mind saw relief in this outside thing, they were like, “I’m not going to even try to give you any healthy defense mechanisms or coping mechanisms.” My emotional evolution stalled around the time I started eating and using an excess.

I’ve never heard that part of it explained that way. It makes a lot of sense because what are the things that would motivate us to get out of the suffering? It’s like, “I can eat a donut,” or whatever. It’s a great point. It’s threats and bribes. I have three daughters and it’s like, “We’re going to potty train.” An M&M for number one and two M&Ms for number two on the toilet. With Max, is there a different practice that you’ve put in place? It’s like, “Dessert is fun. Eat your vegetables, then you can eat dessert.” It’s normal and we don’t even realize it. Has that played out differently for you as a father?

I have a normal approach to food or whatever that looks like. Growing up with my mom, I was going to like Weight Watchers meetings with her. I was like, “You ladies like to talk about food a lot.” I’m on my Gameboy in the back and she had no one to watch me. My wife’s side of the family has a quasi-normal relationship with food. To my son, I try to make it not a thing but also to learn to not give him bad habits such as the thing that I grew up with, which was, “Clean your plate. Push past being full because the famine is coming.” I can appreciate that till maybe 100 years ago. “It’s all right. God willing, we’re going to be able to go and get some more food.”

What’s beautiful about little kids until they’re 2 or 3 is they only eat until they’re full. They’ll even have beautiful mac and cheese still sitting on their plate and they were like, “It’s done. I’ve eaten.” If that was me and you put mac and cheese on my plate, I’m going to kill the whole thing. They already know. For example, when he gets older and he’s like, “Yay, out for school. Let’s get ice cream.”

It was explained to me like this and this is how we do it. We model, “This is how we eat,” 80% of the time. We’re eating like this in this house. We don’t necessarily make special meals for the girls. When they’re little, we’re not going to ask you to eat the kale salad. We get it. You’re not going to give watercress to them.

The other side of it is not to make anything taboo. We eat a certain way. With my girls, I’ve seen it already two times, they do go back to the habits. It’s an interesting thing like, “We’re not going to make it a thing. It won’t be a reward,” but also, “Do you want to eat a chip? Do you want to have Cheetos? Do you want to eat some weird fast food? Knock yourself out.” Making anything forbidden is usually not the way to go.

Sometimes if I’m putting my son in his pajamas or getting ready for school, I’ll look at his tummy and his chest for a moment and I’ll be like, “It’s so perfect. Don’t mess this up.” I know the effects being 100 pounds overweight has. No matter how good of shape you get in, there’s always going to be that bit of scar from where you were. Stretched-out skin, stretch marks, and all of that now are something that I can own and feel comfortable with.

There is a small part of me that goes, “I want you to have trial and tribulation. I want you to have to face difficult things, walk through it, and be a better man for it,” but not everything. I’m fascinated to hear about how you and Laird approached it because we want to give our kids this great life and we don’t want them to necessarily have all the challenges that we had. Yet you’re always walking that line of, “How do I now make this kid tough?” It’s hard.

Armor up. You need a certain amount of armor in life. It’s an interesting time that your son is growing up in. There were helicopter parents and now there are snowplow parents. Snowplows try to take everything hard out of the way. Before, it’s helicopter. It’s like, “Where are they?” Now, we have snowplow. They don’t want to have any attention.

Here’s what I know when it comes to that thing. You will give Max more than you got and you’ll start thinking, “He has a good education. His mom and I love each other and we’re kind to each other, and that’s going to take care of it. He lives in a clean, safe environment. We’re not beating him.” We have a checklist of what we wanted. What we don’t realize is this world, this life will give them challenges that will take you a second to understand.

For example, expectation. Max will work with a different expectation of being successful. “What are you going to do? Are you going to be funny like your dad? Are you going to be a performer?” Nobody ever said that to you because you and your mom were making it. We joke in our house, “If you were sober and paid your rent, that’s good. That was our expectation.”

Even though we’re not selling them that and we’ve provided this great environment for them or a decent one, the outside world is putting a different message on them. Their destiny is not your destiny. I see it and I go, “These girls have it so easy because they’re not living the life I lived.” So often, we put our template on top of them instead of realizing it’s their own thing.

Have realistic conversations. Your son’s going to go through hard times. You’re not going to try to shield him from every hard time and you’ll listen. That was an important lesson for me as a parent when your kid is like, “This person was mean to me.” It’s not making excuses or anything. Just being like, “I’m sorry, that must be hard.” What they’re also learning is how to express their feelings. The fact that Max will tell you, that’s the magic. You want him to be able to say what he’s going through. He’ll find the way to work it out. It’s brutal to watch. We think if we check certain boxes, our kids will get to avoid certain pain, but they won’t.

It’s amazing giving people the dignity of their own experience.

Josh Peck – Love is this idea of allowing someone to prove themselves over and over again through time, through challenges.

The dignity of their own ass-whooping, too, on top of it. As the parent, because you’re not objective, it gets easier. You practice it a little more because it’s somehow some kind of faith about, “This is how life is.” Imagine, your son is precious. You never want anything. It’ll be there and if you guys are there to listen, that’s powerful.

In general, I feel like if you’re doing some good growing, you’re talking less every year you’re alive. Especially how much unsolicited advice I gave throughout my whole life to everyone. It’s also a way to feel like I can control the world. Self-will and run riot. As long as you act the way you should, we will have no problems. Everything will work out fine and drive the way I think and serve me the way I think.

My wife has done such a good job of getting me to shut up. I’m fascinated with people like my father-in-law. He was a professional athlete. This kismet universe put him in my life as a great role model later in life. We talked about certain natural alphas like Laird and whatnot. This ability to present this calming energy without having to display it or perform it or overtalk it is a temptation because I love to talk.

There are some things that I feel are important to talk about from your book. This reminds me now of where you must be right at this moment. Spoiler alert, you went through this whole process, you achieved success as an actor, then you achieved success and financial success using social media. You’re an early adopter who has a skillset that works beautifully. You readdress going back into acting and even going to acting classes as an adult.

What’s so beautiful is how you’ve come around to, “I’m going to do this because I want to.” The stillness within that that you seem to have come to with doing it because you want to, not because of the outcome, which in your job is hard. Because the outcome is you got the gig, you didn’t get the gig, you’re still in it, it has been your comeback. It’s all that BS label stuff that everybody puts on all these unsustainable things. It’s interesting because you say that about your father-in-law, but I feel like you’re getting versions of that stillness showing up in your own world.

Anything that I thought was my identity, I had to go through ego death. I remember once, I was talking to a guy I’ve known in sobriety for a long time and I was going through it again. Especially in my business, every couple of times a year and that’s a good year of being like, “It’s all over. This is the last one. It’s the last time I’m going to be rejected. It’s the last time I’m going to take a no. I can’t take this anymore.”

I remember saying to him, “I’m embarrassed.” He said, “Why?” I said, “I feel humiliated. I feel like I am this guy and I was a successful actor for so long. Now you all see me struggling and I hate it.” He said, “Josh, first, I don’t think about you that much. When I do think about you, a small percentage of that is Josh Peck the actor. About 90% of it is you as a human. I like my friend Josh. He’s a respectable guy. He’d probably pick me up from the airport if I ask nicely. The important things. That’s what I think of you. If there are people in your life where the majority of that ratio is thinking of you as an actor, they better either work for you or maybe you don’t need them in your life.” I found that to be incredibly true.

I had all this success till I was 24 years old in acting traditionally. I also had burnt out on being so at the mercy of the gatekeepers of producers, executives, and these people who would make decisions for my life that I had no power over. I found social media fabulous and it was lucrative, but all of a sudden, five years into it, I’m like, “No one’s calling anymore.” I did love acting but suddenly, I’m in this position where maybe that part of me is going to become forgotten.

It was facing all these different things to eventually get to that place of like, “What do I want if it’s not my identity and if it’s not important to me what you think of me? If I’m alone and I’m looking at myself, what’s my truth?” It was that I enjoy acting. It’s something I’ve done since I was a kid. I fell in love with it when I was 10 years old, not thinking about money. If I can still do it, I’ll do it. It was one of the first times I was able to walk into an audition into an opportunity freer than I’d ever been.

I want to promote The Wackness and you have a show on Disney streaming.

I’m on a show now on Hulu called How I Met Your Father and I did a show in 2021 on Disney+ called Turner & Hooch.

It’s all of the old things about when you let it go and you pay attention to what you’re doing and not worry about the outcome, and then all of a sudden, you’re having this next wave of opportunity. It’s like dating, too, sometimes. Desperation never smells good.

They smell it on you. It’s the worst.

I always think about this even in business. I’m like, “Check yourself like.” You can think that you’re putting on a brave face or no one knows, but people can smell it. It never works. You go from 16 to 19 doing Drake & Josh, you do some films, you do Snow Day, you had done The Amanda Show prior to that, you’re an adult, you lose weight. Let’s talk about that. You make it simple. I know you don’t want to hear it but it’s like, “Eat a little less and exercise a little more.” For somebody who’s going, “I’ve got stuff to tackle,” how do you start on both sides?

This was the early 2000s. I did early keto, also known as the Atkins diet. Poor Dr. Atkins.

He died and they rebranded.

They made him evil. They were like, “Eating bacon, that’s crazy.”

“That’s going to kill you.”

He knew. Shout out to Dr. Atkins. RIP. That was such a hard chapter to write when I first decided to start losing weight. My friend, Ryan Holiday, who helped advise on the book, said, “This is the turning point of your life. This is the most important chapter. You must write it so that a 16-year-old version of yourself would maybe cry reading it.”

I had to talk about how I was so sick and tired of being sick and tired. I tried everything. I’ve done it my way and it got me incredibly overweight and unhappy. I say that to the people who are reading the book. If you are at that place where you’re utterly over it, feel hopeless, and you can’t take it anymore, I have empathy for that because I know how painful that can be. I almost want to say good because I don’t know where change comes from unless you’re thoroughly uncomfortable. At least that’s what I can speak for myself. Pain has been the great motivator of my life. If you’re over it, great, now what? I would start these crash diets. At 295 pounds, I’d lose ten pounds in three days and it’d be awesome.

The body wants to let go of it. There’s this thing where if we do have an excess of weight, we will get a big beginning, and then sometimes there are plateaus and things like that. You would go ahead and lose ten pounds quickly, but then what?

It wasn’t sustainable to be that rigid. Inevitably, I wind up giving up on Wednesday and eating poorly until the next Monday, and it would just be Groundhog’s Day. I remember at 17, my mom and I went to New York to spend the summer there. We’d had these long conversations in the car. I finally was starting to face the stuff with my dad and letting go of some inner emotional anger, which I had been medicating with food and everything else. Instead of facing that, it allowed me to say, “What’s this other thing?”

I knew that at 17, I was crossing this invisible boundary. I had already felt I’d missed out on some of the teenage experience from feeling too insecure to participate. I’m like, “Am I going to miss my college years because I don’t feel confident enough to go to the party or to have a girlfriend?” Whatever that version is for a child actor in my early 20s.

[bctt tweet=”The teacher will reveal themselves when the student is ready.”]

I remember we went to New York and I would walk the streets of the city. It was the only thing that didn’t hurt exercise-wise. I slowly started eating better but if I messed up and I had a dessert or something, I didn’t allow it to make my tailspin. I would live to fight another day. I did that consistently for two years. If I plateaued, I would dial it in again. Before I turned 18, I went from 300 to about 180 pounds.

That’s incredible. What about working out where you’re like, “Worst.”

It’s so painful.

It’s the beginning point. Laird has a saying, “There’s only one first day.” How did you get the information to know what to do? Did you just wing it and move around more?

I was mobile, even when I was heavier. I liked being active. My best friend and I would play hockey every day when he got home from school and I would get home from work. I enjoy being active, but I knew I was limited. I remember I went to a tennis camp when I was 12 years old. Did you go?

No. I didn’t have access to a tennis camp.

I don’t know how I did.

You must have done it through the Jewish Community Center.

Shut up.

You were already back in LA by that time. Did you hit it hard?

I went for five days. I was awful. I remember sprinting up and down the court. I would have to lay on the court like this. I was like, “I’m going to throw up. It’s just a question of when.” I knew. I was like, “This is bad. I’ve painted myself into a real corner here.” When I first started to work out, God bless my first trainer who said, “We’re going to do a push-up.” I was like, “Bet. Love the idea of that. Not sure it’s possible.” He’s like, “It’s possible. You’re going to do it from your knees.”

I was like, “Still hard.” He was like, “I’m going to wrap a towel around your waist and I’m going to offset some of the weight I’ll pull up with you as you push up on your arms. We’re going to do it ten times. One day, you’re not going to need the towel, and then one day, you won’t be on your knees doing it.” That’s how I approached pull-ups, push-ups, and sit-ups. It wasn’t until I did Red Dawn years later that I got ground in by true fitness guys.

You mean the Navy SEALs.

Some real dudes.

Let’s put the framework around that. In Red Dawn, you were playing Chris Hemsworth’s brother.

Who made that choice? It’s a little far-fetched. Adopted brother.

You have different fathers in the story and you have the hottest girlfriend ever.

I was in love with her, too. Shout out to Isabel Lucas.

She’s a beauty. “I love you. I have to leave now.”

She’s my girlfriend in the movie and we said eight words to each other. I refused to talk to her because I was like, “What am I going to say?” The moment I opened my mouth, it was all downhill.

With your Josh Peck version of being Chris Hemsworth, it’s so good.

I got cash in this movie. I thought I had arrived. I had done this movie, The Wackness, and I got all this incredible fanfare.

Is this the Sundance one?

I’m 23 and I’m in better shape. I’ve now been given this vehicle. I’m like, “Let’s go. I’m ready to be Ryan Reynolds. It’s about time. Finally, the world is adapting to what I always knew was true. I am a movie star.” First, they say, “We’d like you to work out with these Navy SEALs and get in shape for the movie.” David Logan, shout out. God bless these guys who were so wonderfully supportive and knew my limitations but were also impressed that I was willing to humiliate myself.

I’ll never forget, the sixth workout was on a Saturday. Dave, the Navy SEAL, said, “We’re going to have a little fun with this workout.” I’m like, “I feel like our definition of fun is different.” He’s like, “Do you see this gigantic Mack truck tire that would go on a farm vehicle?” I was like, “Uh-huh.” He’s like, “We’re going to attach a chain to it, we’ll put it on a harness, and we’ll drag it from a mile.” I was like, “Cool. Old school mile or…” I started working out and I got in good shape, but I was still so insecure. I didn’t know what it meant to be a real man, to be confident, to have all the things that I wanted to present because I was this scared little boy in this new body, in theory, living the thing that I’d always thought I’d wanted.

An exaggerated thing like, “Here I am. Here it is.”

“I got it.” I could tell in the workouts, “This certainly isn’t coming to me as easily as Chris Hemsworth, these natural Adonis men that were in the movie.” Every day on set, instead of embracing my superpowers, be it the comedy or the humility that I’ve learned, I started to present a picture of what I thought they wanted, which was this tough, swaggered out, Chris Hemsworth wannabe.

One of the reviewers said that they thought that I had special needs. It was that bad. They were like, “There’s a side of Josh Peck that he’s never told us.” It was so bad. The worst part is I knew it. I talked about it in the book. It was like being a pyromaniac hanging outside of a lighter shop. I knew something bad was going to happen. I just didn’t know when. For the four months that we’re filming it, I’m like, “I’m blowing this. I knew it.”

How come you couldn’t just pull back on it? You were in and that was it?

I didn’t know there was another way. To the best of my ability, I thought I was muscling it. I talk about in the book the duality of ego. That ego had gotten me to this point and told me when I was 300 pounds like, “You’re a movie star. You’re going to be attractive.” In many ways, it helped get me through those moments where it was like, “If I’d face the realities of where I was at that point, I might have given up.” As soon as I got there, that same ego turned on me and was forcing me to be this BS version of myself that I would never live up to. It was not attractive and wasn’t cool or confident. It was sweaty and trying too hard. It was so bad.

I know with Chris Hemsworth, for most people, it’s like, “It’s so nice.”

That’s the worst part. Gorgeous, perfect, about to go do Thor, a guy, and like “How are you, mate?” I’m like, “I’m great, Chris. I’m better now that you’re looking at me, but I don’t have high hopes for my performance.”

He has a different journey. Nobody’s asking his parents, “How do I make Chris’s life hard?”

Josh Peck – I feel like there are no bad decisions in life. It’s either the right one or you had to take the other one so you could go through the pain and the trial to get you to the next right one.

Am I proud of my journey? Yes. Would I have traded it with Chris Hemsworth in the second? For sure. I’d give it all up.

It’s like, “It seems like he has a nice marriage, family, and he’s humble.”

He’s the whole thing. He’s happy.

I was like, “Maybe.”

I don’t think this is talking out of school here. I remember he had met his wife right after he filmed Thor and we became friends. This is a testament to how cool he is.

Did he still talk to you after that movie?

Yeah. Then one star came out and we lost touch. People get too famous.

They changed your phone numbers and stuff.

It’s hard to stay in touch, and I get that. I remember he was talking lovingly about his girlfriend at the time. He’s like, “We’re probably going to tie the knot soon.” In the back of my head, I was like, “You have Thor coming out.”

“There’s a lot you’re leaving on the table.”

“It’s an exciting time in your life.” He couldn’t have cared less. He’s like, “I found this fabulous person. I want to get married and have kids.” Maybe his parents should write a book.

A couple because they get the other boys, too. They seem all well-adjusted, even the one who isn’t famous. He has two famous brothers, but he still seems okay.

They all seem awesome.

The Manning should do one, too. They’ve got the two quarterbacks and then one who couldn’t play but they all seem okay.

The Manning seemed great.

I know. I don’t get it.

Forget about it.

It’s not our deal. I can keep you here forever, but I want to know, what is your moving and eating life look like? How are you sustaining it? What are you doing? What do you like?

I work out about six days a week.

Because there’s only seven in the week so that’s good.

No big deal. I tore my pec doing bench press and CrossFit. It was the best shape I was ever in. I also got injured and was like, “This probably is not sustainable.” No hate on CrossFit.

You needed to be a college gymnast to sustain CrossFit for seven years without being broken. It’s a different deal. I admire the diversity. It is a tough thing. It would help to be more compact, usually. It’s more for people who have been physically connected most of their lives. It’s a hard gig.

It’s unbelievable. This is how it works for me. I’ll do three days of cardio, even if it’s an hour on the elliptical and I can tune out and watch, catch up on a show. I’ll do three days a week at this boxing gym that I love in Hollywood that I’ve gone to for over fifteen years. This guy, Justin Fortune. I like that there’s one mirror for shadowboxing. Nobody’s there peacocking. It’s old school like sledgehammers, kettlebells, pull-up bars. There’s a weight rack. I turn on a Tabata app on my phone. It keeps me accountable. It’s nine eight-minute rounds. For each round, I’ll try to do two exercises but it’s only a weight that I can do sustainably for those rounds, so it’s lighter weight but I’m keeping it going. I do a lot of push-ups, pull-ups, and squats.

Laird and I talk about this a lot because there’s a price. Ask any athlete, they’re broken. I have a fake knee and he has a fake hip. There’s always a price for some repetitive motions. Laird’s like, “If you think about it, in the old days, we ran and then we laid around a lot.” I appreciate what you’re saying, because it’s about doing a little bit all the time, a little bit good to go err once in a while, get the heart rate, get that up, a burst for a moment. It doesn’t have to be a death every day that you live in the gym. What about food? Because I would imagine food would be the bigger obstacle. If food was the friend for so long, how’s that going for you?

I am eyeballing the caloric content of everything. It’s not macros. I try to consume much more protein than fats and carbohydrates. I try to allow proteins to be the predominant thing and then fats, and then, inevitably, carbohydrates.

Carbohydrates can be your salad. They don’t always have to be so evil. It’s important for people to understand, carbs are in a lot of things, including salad. It’s not like you’re talking about a bowl of pasta necessarily.

But how good is pasta? How often do you eat pasta? Do you eat pasta?

Absolutely. I was just on a trip. I don’t take many trips outside of work. Is there anything harder than a vacation with your family? After the second day, it’s like, “Okay.”

You’re like, “Why did I do this?”

You’re fighting at the airport on the way home. I did have pasta there. If it’s good, I’ll eat it for sure. It’s just not part of my everyday. The 80/20 rule, I live by that. Have you found that when you don’t consume it that you don’t jones for it as much?

Certainly. If drugs and alcohol are your things, it’s a blessing because you can just cut it out. Food is a different animal. In a weird way, since I was 19, I’ve enabled to keep the weight off. I don’t weigh myself because I’m too obsessive. I can tell by how I look and from clothes that I vacillate probably 5 to 8 pounds, depending on where I’m at, what I’m trying to do, and my training schedule.

When I get an office job, I’m like, “I’m 188 again.” When I’m not working, I’m like, “I’m 198 again.” I feel lucky that for me food is this thing where I never wake up in the mood for a salad. I’ve somehow been able to manage it like a normal person. I have people that are close to me who weigh and measure their food because there’s no version of normal eating for them.

I know what that is. I had to do that with drugs and alcohol. I tried to drink like a normal man. I counted my drinks. Certain people will say that. A lot of people would be like, “I make sure I only have 2 to 3 drinks.” I heard someone say once, “If you’re counting your drinks, you don’t have a normal relationship with alcohol.”

I do appreciate that the first drug you try is cocaine. That’s big when a girl is involved.

I was in love with that girl.

She offered it to you once and you said no, and then she came back at it. I want people to read your book. I’m not going to go too deep into it, but you have a journey through addiction. If you’re open to it, you got a letter from a producer getting released from a job. Drugs are a part of this. As a comedian, to get a letter from someone like this would probably be a good wake-up call of sorts or part of the wake-up call. This was on for four years, right?

[bctt tweet=”Love is this idea of allowing someone to prove themselves over and over again through time, through challenges.”]

Yes. When I turned 18 and I was getting to the tail end of losing all this weight, I suddenly had the same head in a different body. I didn’t have my medicine anymore. When I found drugs and alcohol, I was like, “This is so much more efficacious. It works way better.” I took that deep breath that I’d always been searching for my whole life and I was like, “If this is possible, why would you ever want to feel any other way?”

I thought I presented what I’d wanted to present my whole life, which was Chris Hemsworth’s version of Josh Peck, confident, attractive, and funny. I chased that feeling for four years. I didn’t take a sober breath for that entire time and it resulted in a lot of things. I had the proclivity for calling the police on myself because I thought there was some incentive if you were the first to alert them, but there isn’t in case you’re wondering.

I like when the guy flipped out on you on the road, you called on him, and the lady’s like, “We’ve had seven calls about you.” I wonder if you were that wild, Josh.

Me either.

“I’m a bad boy.” Maybe you are more Chris Hemsworth than Vin Diesel.

Tell your friends. Put that out there. I was on this vision quest for four years sowing my wild oats and I wound up getting this great opportunity in the middle of it as things go to be in this comedy with Owen Wilson and Danny McBride. It was written by Seth Rogen and produced by Judd Apatow. If there is ever a great team for a funny Jew such as myself, that is a team you want to be on.

To Judd’s credit, besides being insanely talented and having so much success, to me, one of his superpowers has been being able to recognize non-typical leading men like Seth and Jonah Hill and giving them vehicles to be great. For better or for worse, he saw something in me and gave me this opportunity. I just was not in a place to take advantage of it.

I don’t think I said this in the book, but I remember one day on set, we’re watching some playback on a monitor and Judd said, “I’m working on this other movie.” This is before I screwed everything up. He’s like, “I’m working on a southern movie right now. You should come by the set. Maybe you can think of something funny. We’ll put you in a scene.” I was like, “Yeah. What’s it called?” He’s like, “It’s called Superbad.” I was like, “I’m busy.” I’m sure that didn’t affect me negatively at all.

For the next couple of months, it wasn’t like this act of explosion, but it was a lot of being selfish, unreliable, showing up late, and not being completely there because I wasn’t completely anywhere. It resulted in me getting a polite yet tough email from Judd saying, “You’ve come late a lot and it costs the production money. You’re a talented guy, but this will never fly here or anywhere else.” I’ve said it in person, but Judd gave me an incredible opportunity. He couldn’t have been a cooler guy and I just wasn’t in the place to take it.

I had to live with that for many years, the shame of that, the frustration of squandering an opportunity. Inevitably, it all worked out because I had to do what I had to do to get here. It was facing moments like that or Red Dawn, or all these inflection points where I felt like had I been able to take proper advantage of it, it could have resulted in something big. I don’t know how you feel. I feel like there are no bad decisions in life. It’s either the right one or you had to take the other one so you could go through the pain and the trial to get you to the next right one.

What’s beautiful for you is that you did it early. It’s always hard to watch when people squander lots of opportunities because as you get older, you start to realize opportunities are precious. It’s like having a good friend. When you’re young, if you have opportunities, it’s easy to misconstrue that, like, “They’ll be there and it’s going to come again.”

You always hope that people dial that in sooner so that they can continue to express themselves more fully as they go through life and all the lessons. When people talk about failures, it’s the same as blowing it a few times. Because when the door comes for you again as it does now, you’re probably clear about like, “This is something I will take care of, be it show up on time, know my lines, all these other things.” You probably appreciate it differently. It’s all a perfect story for all of us, but it’s hard sometimes to feel that way on the times that we think we blew in moments.

It’s certainly ego-reducing. I talk about in the book that at the moment where this massive shift in so many good ways of getting married, having a kid, and then inevitably having the second act in my traditional career, it was that ego death. It felt like my pride was in the tenth round looking for a knockout. It was like, “I’ll do anything to get you miserable.”

I heard this woman speak once and she’s like, “What are you willing to give up that stands between you and happiness?” Because we all know our character defects to a certain extent, hopefully. We’re all like, “I have too short of a fuse. I get angry quickly,” or, “I’m too jealous.” Those we’re all willing to let go of because they’re ugly.

My wife gets pissed at me because I get too easily frustrated, but then there are more nuanced things that are intertwined with our make-up. I remember this woman said, “Once you get rid of the obvious defects, what are you willing to let go that you think defines you? Is it that job you think you can’t live without or that relationship that you think you can’t live without but isn’t working for you? Those are the things you might have to give up on your road to happiness to know that you can be okay without them.”

That’s what I faced at 32 years old when I called a friend at a total bottom and said, “My life is so good. I have all the cash and prizes that come with a great life. I have this great wife, this great kid. I’m more than making a living. I’m doing great. There’s this one thing, this acting thing that’s killing me. I worry that if I don’t let go of it, it’s going to separate me from how good my life is. It’s going to stand in my way of truly enjoying this.” It wasn’t in the letting go of who I thought I was. It was facing the anomaly of my childhood and not letting it define me that allowed me into that place of stillness to walk forward and do it on the right terms, not just because my ego thirsted for it.

It’s okay sometimes to say when you do something that it does feel good when somebody goes, “Great job.” That’s okay. Where does it live? How much does it drive us? “Now I can be validated.” My favorite is when you get attention and the opportunities, and then all of a sudden, they slow down. There’s nothing like that kind of ass-kicking where you’re like, “Nobody is calling. The phone isn’t ringing.”

When you look and you have real friendships, you have a real relationship with your wife, and your son looks at you because he adores and loves you because you’ve invested time with him, that’s still always going to be the stuff. It’s the thing that we get to participate in. The rest is like, “We’ll see how that goes.”

Josh Peck – For most people, food is their first foray into using something to numb whatever’s going on, whether we know it or not. It certainly is societal. It’s used as this reward system.

My friend Paul Gilmartin tells the story of a buddy of his who was talking about summiting Everest. He’s talking about the last couple of feet and then arriving at the peak. Paul said, “When you arrived there, did you find your father’s love? Was it there at the top of Everest?” It’s all these things that we say if only, then… “If only I achieve this, then I’ll find Nirvana.” Euphoria is a few more steps down the road or contentment and it’s like, “It’s got to be right here otherwise.”

It’s in that next job.

If I can get a six-episode arc in succession, it’d be a whole lot better. I know it.

The same year, the cover of People magazine’s Sexiest Man Alive. You’re done. It’s perfect.

They’re going to airbrush abs on me.

That will be amazing.

I’ll spray tan for that.

All-day long.

For the cover of People, I’ll get a number three.

Ryan Reynolds will be super jealous. You did a film with Ben Kingsley. He’s an actor’s actor. The guy is a G. You at the end were like, “Do you have any advice?” He said something important for all of us.

I did this movie, The Wackness, at 19 years old. Sir Ben Kingsley is the lead of the movie and I’m playing opposite him. He’s my Tom Brady. I love the guy growing up. He’s the one I looked up to most. At the end of the film, I remember I had a few minutes left with him and I was like, “I got to ask him for some advice.” I remember asking him and he looked at me, cocked his head almost to say, “Really? You’re going to make me answer this?”

He knew you didn’t have a dad. You’re trying to get some information.

Who doesn’t know at this point? I lived it like, “I’m Josh Peck. Never met my dad. Trying my best.”

This is a big deal.

He looked at me and he was like, “Find your apostles.” I said, “No. I mean how do I become the biggest actor in the world?” I was like, “I’m Jewish. I think that’s more of the New Testament deep track apostles.” One of Moses had apostles.” He was like, “Find the people that you feel make you better that you want to share your wins with and your setbacks with, that you will look to their counsel for the moments of complete and utter success and also strife and frustration. If you’re in a room of people where you feel any other way about them, I would suggest you leave immediately.”

I say in the book, the teacher will reveal themselves when the student is ready. I wasn’t ready to hear that at that point, but this idea of collecting these people in your life always stuck with me. I always say, “If you’re wondering if the person in your life is an apostle, think of someone who recently said something to you that you didn’t like but you knew they were right.” If we were capable of hearing it, we probably would have come to it ourselves. When an apostle speaks to me, I have this immediate reaction of like, “Screw them. I’m the worst. They’re probably right but it’s too late. Fine, I’ll do it.” I’ve been lucky to have a few people like Sir Ben in that way.

What have you learned being a husband? You stayed. You’re in. I experienced this. Laird taught me vulnerability. I always split.

Me, too. I’m that way.

My mom left first. She took a little parenting hiatus from age 2 to 7, and then my dad passed away when I was five. Laird tells a story often that I said to him when we were dating, no one is above my survival. I didn’t even finish it with, “That means you.” That was my mentality. I can’t even believe I verbalized that. It takes courage to be vulnerable. It’s not the other way around. I wasn’t stronger because I would leave an uncomfortable situation or not be confrontational. You’re in a long relationship and you’re married. What have you learned about what it takes to be a partner?

I resist this idea of love at first sight or I fall for them right away. I don’t know if that exists. If it exists, it’s not love. To me, it’s attachment and lust. If love comes eventually and it turns out that it was all this perfect storm, great. I always say that love is this idea of allowing someone to prove themselves over and over again through time, through challenges.

I always say that love is when you have food poisoning and your partner is getting you Gatorade and making an appointment at the urgent care and not judging you for whatever’s going on in that bathroom. Like happiness, love is an action. My wife holds me to such a great standard. She forces me to look at my BS, my defense mechanisms, my desire to always be shticky, people-pleasing, and allowing me to honor my deeper truth, the things that turn me on, the things that get my soul excited. She’s taught me restraint of pen and tongue, not to talk so much.

One thing I respect about her so much is she has this way about her of what’s acceptable and unacceptable in a public forum. It has forced me to clean up my act. I see the way she treats her elders or peers, or even people that piss her off and annoy her. It’s a great trait that she shares with her dad. It’s like this ability to be the water, not the rock. She doesn’t have to dig her feet in and be heard. It’s like, “If this is an uncomfortable situation, we can move past it. We don’t have to make a stand.”

I’m happy for you.

I’m happy to know you.

I want you to know what I see. I see you as somebody so lovable but not because you’re funny and it has nothing to do with performance. You are a person who listens whenever we engage and I feel your presence. The fact that you’re curious and willing to take a look at it. When your friend said 90%, I get that. Whoever gets to know you is fortunate on whatever level.

I appreciate that you wrote this book, Happy People Are Annoying. There are a lot of stories in here that are heavy. When I say that, I mean they’re heavy topics. You did a beautiful job of not making too light of it and you did make it entertaining. I appreciate it because it’s not easy to do and it takes a lot of courage to say, “This is who I am and some of my stories,” and share those with people. There are going to be a lot of people who resonate with this. I want you to tell me about Sharon because Sharon feels important to me. I feel like we all need moments where we have Sharon’s come into our lives to kick us in the ass a little to help us.

I gave you a shout-out in the book.

I was surprised. Nobody told me. I was reading the book and you did because we pool-trained together.

[bctt tweet=”A great teacher can hear the wrong note and teach you how to fix it.”]

You and Laird, there’s a beautiful quality about the both of you. That’s such a metaphor for all the times that I’ve been lucky enough to hang out with you guys. I had a podcast years ago and I said, “Who are the people that I look up to?” This is me talking through the lens of 16-year-old chubby Josh. It would be easy to look at you and Laird and think of you guys like the Tom Brady’s, like, “They’re attractive. They’re fit. They have it all.”

We’re meatheads.

You’re the goal. I’m like, “These people are nothing like me, but I look up to them. I’m a fan.” I remember reaching out over social media. Having people far less famous and people far less as accomplished as the two of you give me a harder time about interviewing them for the podcast. You guys got back to me immediately and said, “Whenever you want to come, let’s do it.” Already, I was like, “I’m walking into this warm environment.”

Getting to interview the both of you, these two different interviews, being invited to train, you having this moment with me in the pool where you spoke directly to me. I remember you lead with, “You have a strong mind.” You gave me this feeling of like, “I appreciate that you’re here and trying to keep up with this so I’m going to speak to you in a clear way. We can make alterations to the ways in which you’re not at the elite level that we’re at yet. As long as you’re here meeting me, I’m willing to shepherd you along this journey.”

That’s so important. That speaks to who you and Laird are. Whether it’s allowing some schmo to come over and interview you or being in the pool or what have you, that’s it. Laird and I are talking about it in the sauna that it’s like paying it forward, this idea of taking all this goodness that you’ve accrued in your life and saying, “Who’s in the next generation? Who can I pass this along to?” I love the phrase, “Help your fellows boat to the other side and yours, too, will cross.” That generosity is a part of your secret sauce.

It’s also selfish. I want to keep that flywheel spinning. I don’t want it to stop. It’s interesting, Lair and I are different. Even though he seems to have this exterior a little gruffer, I’m the more calculated. Somebody said to me once, “You seem so humble.” I’m like, “I don’t think I am humble. I just think I know the laws of the universe. I know it’s better.”

What happens is if you live that way long enough, you start to experience how you can connect with people. Maybe with an initial thing like, “If I can help or say yes, I should,” and that flywheel, and then you realize, “It’s the only way to live.” When someone is willing to show up, it takes balls, it takes courage. For someone to go, “Can I come?” You go, “Yeah, come on. I’ll take care of you.” Thank you. Tell me about Sharon.

I did this show with John Stamos when I was 29 called Grandfathered. It was this big, exciting moment. I’d been on social media for a while and now I’d booked this big TV show. They were like, “This is it. You’ve arrived.” I remember that slowly but surely, every week, the viewership went down almost to the point that towards the end of the show, one of the crew members said, “I’ll see you next season.” I was like, “I doubt it.”

The show got canceled and it became clear to me that I had had these blind spots that I had accrued that I started seeing on Red Dawn seven years prior. I said, “I know I can be good. I’ve certainly had a healthy amount of success, but what did I attribute it to? I lacked consistency. I can be good or not good. I was like a football player who does great at the Combine, but can’t play on game day.”

I talk about how I was a fighter with a record of 20 and 20. You want to say to people, “I was fighting at Madison Square Garden a couple of years ago.” They’re like, “Yeah, but now you’re at a Ramada.” Things have changed. I knew there were these blind spots and in a deep way, looking at these blind spots, I was using it as this defense mechanism to save me from the idea that if one day, things didn’t work out the way I’d hoped, I would have this slight failsafe. This idea of like, “I never gave it 100%. I didn’t give all of myself.” Who wants to be that vulnerable?

I was lucky enough to have an apostle in my life, Vincent D’Onofrio, a brilliant actor who happened to be my manager’s client as well. We were having dinner one night and I don’t know why but I asked him randomly. I said, “Do you know of any good acting teachers in LA?” He’s like, “There’s one and her name is Sharon Chatten. She’s been my teacher for twenty years. She’ll teach you method acting the way it was taught in The Actors Studio, which was Pacino, Paul Newman, and the greats. If you want to invest, she’s the one.” I said, “Great.”

I didn’t call her for two years because I had more bad acting to do. I knew that I was at this impasse. I knew that I was at this inflection point that if I never faced this thing, I’d probably get more opportunities, but it would never be the thing I wanted to do. Eventually, I’d accrue enough bad reviews to where I wouldn’t get an opportunity.

I called her one day in 2017. I walk into her class, I stand there, and I begin this scene with this other actor. She stops us within twenty seconds and she proceeds in a way you might approach it, which wasn’t mean but it was brutal. It was honest and direct, all the ways in which I was a fake. She didn’t say that I was a fake, but she made clear that I was not doing what was required to be good.

Everything’s firing in my mind like, “I’ve accomplished so much. I’ve worked. The business told me I was good once, but what happened?” I had to face that for four months straight every week, walking in there and being pilloried and accepting this idea of like, “I don’t know what I’m doing.” Laird said this when I interviewed him for the podcast, “So few people are willing to begin again and to be students again. They accrue enough success and they get old enough to where they’re too resistant to being uncomfortable.”

For four months straight, I sat in that class and looked at these people who probably watched me growing up and was like, “I suck. I’m the worst in class. Jane from Omaha who’s only been in school plays and Rick who’s 26 and has only done commercials, here I am a guy who’s done a fair amount of stuff.”

Slowly but surely, I got better. I allowed what Sharon was teaching to enter into the way that I approached work. I learned the basics. Acting to me always seemed like this weird alchemy. You were either good at it or you were not. Through going to class every week for years, I learned that it’s a grouping of the basics. There’s an alchemy to it, like anything beautiful and artistic.

There’s a lot within your power that you can do to put your best foot forward and make it good if you’re willing to do the work. I just didn’t know what it was. Sharon is still my teacher to this day. I go to class every week. When I’m working on something, then we’ll do private sessions. What separates a great teacher from a normie is you don’t have to be a musician to know when someone plays on the wrong note. You just have to have ears, like, “That doesn’t sound good.”

A great teacher can hear the wrong note and teach you how to fix it. That’s what she did for me. She was like, “Here’s where the inconsistencies are. If you double down on the basics and the fundamentals and learn the thing that you think you’ve given your whole life to, good things will come.” I’m so glad I did it.

It’s that reminder, which is a craft that she taught you, to have tools, which I would imagine gives you so much confidence. If you go in for an audition, which is already intimidating and scary. I don’t care who you are, those things are not set up to be easy. They’re brutal. What a gift to do something for so many years and now be like, “I have new tools. I can come in and I can navigate my way in and out of situations.”

People get scared thinking, “I’m supposed to know.” It keeps us from asking for help. It’s like me and my own fitness life. I have so many things that I try to work on or I need to work on and I need to get help because I’m moving the wrong way or I’m doing something wrong. It’s interesting to feel like “I’m supposed to know.” You need to get help, like, “I need new information.” By the way, I go to places and someone will be helping me, and I am bad at it. Some of my movement patterns are the worst.

You can make up for it because you’re so adept in other ways.

It’s going to get you. That’s your thing. It’s going to turn into an injury. It’s going to turn into something. I wanted you to tell that story because we all experienced this maybe in our work-life. Maybe we’ve been the manager of something for 15 or 20 years, but the world is changing so we need to go find someone a little bit younger and go, “How is this working now?” Not to be afraid of that because that is a lot of power. Staying curious and open and being willing to be like, “Even though I know this over here, I don’t know this over here.” I appreciate that story. Thank you and shout out to Sharon because she sounds like a badass.

Happy People Are Annoying

She takes no crap. She’s sharp and awesome. I’ll never forget at around three months into starting to take her class, I was feeling like, “Oh god.”

Did Paige have to prop you up each time and send you out the door?

Her classes would be from 7:00 PM and sometimes it would go as late as midnight or 1:00. I’d come home and I’d be like, “Think of having another kid yet?” Sped up spirally.

“Wake up, Paige. I’ve got to tell it to you.”

“You know the whole thing that keeps all the lights on here? Apparently, I’m awful today.”

“I’m the worse. You sure you want to be with me?”

“This is bad news for all of us so get out now.” “It’s fine. We can go drop the papers outside.” Another credit to Sharon being a good teacher, she was in tune with where I was at mentally.

Would she ease off of you once in a while?

Yeah. By the way, three months isn’t that long. I remember that one class where I knew this scene and I applied everything I learned over those three months. Her watching and going, “That was so great,” I was like, “Oh god.” That turning point. I had a couple of great weeks like that. Eventually, there was a slight bit of like, “I’m going to wear you down a little bit to open your ears, and then once you can hear me, then I’m going to support you.”

I remember she called me and she’s like, “You’ve worked a lot. It’s hard for you to be bad. I see that in a lot of people who’ve had some success. The Actors Studio was created to be a gym for actors by Lee Strasberg in the ‘60s and ‘70s. This idea of, ‘We need a place because it’s hard to act,’ is not like guitar or painting where you can do it while you’re alone. You need a safe space. It’s not in front of the camera all the time to try things.”

She’s like, “I would watch famous people come to The Actors Studio and try things that were out of their wheelhouses like Romeo and Juliet or something that they would never think of doing in their traditional career. Sometimes, they fall to tears because it’s not what they were used to and not what they were good at. Bravery would come over them. They faced this giant and they knew that they were growing and that they’d get there, but they had to be willing to be bad even though out there, they were on billboards.” That stuck with me, this idea that I’m sure some of my heroes have maybe been in a similar position. Probably not Chris Hemsworth.

He probably could even slay Romeo and Juliet. He could do it for sure. He has no problem. He’s happy every day.

Do some Shakespeare for all of us.

I get when you say that the growth is also reminding us that we’re not being a fraud. We can be a lot of things simultaneously. To give ourselves that room to do it is great freedom. For example, Paige, your friends, your life, and your work, all of that will grow with you because you’re growing. Those will continue to be enriched. People don’t realize the impact of trying new things and being like, “This is so scary.” It’s also a practice. I guarantee you that after doing that, you can do that easier in your life. You’re like, “I’ve done some scary stuff. I’m still here and I can keep trying.”

What still scares you?

Parenting is always something I’m concerned about. I try not to be scared of it, but I know it’s something that scares me. I’m trying to pursue things that I’m genuinely attracted to and take them all the way over the line. I was talking to Justin about this. Sometimes, I go, “Do good and be successful, but not too successful.” Because I wasn’t raised that way. I wasn’t groomed to be a winner or champion or whatever BS words we put on it. It was like, “We have a good amount of success. We’re good.”

Sometimes, there’s a part of me that wants to dream. It isn’t about more material things, more money, more attention. It’s about how expansive and how big can you make an idea happen. That’s the thing that I’m always monitoring in myself, which is, why would I limit myself? Maybe that goes back to the 6’0” 12-year-old, which is like, “I’m going to be big, but maybe not too big.” That’s something I try to face.